For the early Celts, Beltane was signaled by the blossoming of the

hawthorn tree at the beginning of May, therefore known as the "May Tree."

%20poster.png)

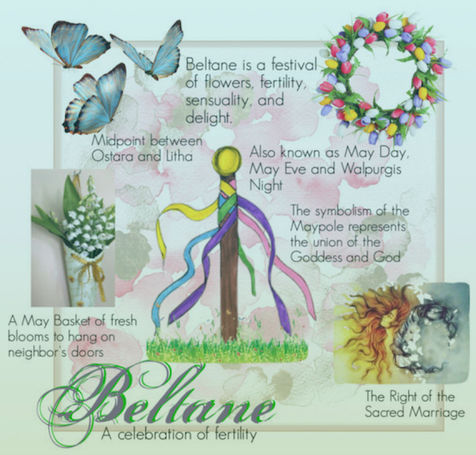

The "Green Root" & "Red Root" Traditions of May Day

This meme depicts the ancient seasonal May Day tradition

This meme depicts the modern sociopolitical May Day tradition

Thematic Images for Beltane Posters

.png)

.png)

Slideshow gallery. Click image to expand, then scroll through images.

Thematic Images for Blessed & Happy Beltane / May Day

%20poster.png)

%203.png)

%203.png)

Thematic Images for Beltane on the Celtic Wheel of the Year & Its Dating

Beltane, traditionally celebrated on the eve of May 1st (“Fixed Date” ), is one of the four “cross-quarter” festivals on the Celtic Wheel of the Year. The word “Beltane” probably originates from the Celtic God “Bel,” meaning “the bright one” and the Gaelic word “teine” meaning fire. Thus, Beltane (or Beltaine) is a “fire festival” celebrating the coming of summer ("Here Comes The Sun"). "Beltane" is the Anglicized form of Irish Gaelic name for either the month of May or the festival that takes place on (or about) the first day of May. In some places, Beltane was referred to as “The May.” Called the “Day of Bealtaine,” it was historically a Gaelic festival celebrated in medieval Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. Beltane also marks a midpoint between Spring Equinox and Summer Solstice (“Astrological Date”), technically a mid-Spring festival. Thus, Beltane is about rebirth after the cold and dark of winter and the sprouting season of early spring. For the Celts, it signified the beginning of the pastoral summer season when the herds of livestock were driven out to the summer pastures and mountain grazing lands. Before there were calendars, many Celtic peoples celebrated Beltane with the first pinky-white blossoms of the sacred hawthorn tree, also known as “the May tree.”

Thematic Images for the

Orphic Essay-with-Soundtrack

Beltane / May Day:

A Holiday for Pagans & Workers

Prologue to Beltane / May Day Musical Essays: Troubadour Spring Poetry/Song "Nature Introductions"

.jpg)

.jpg)

Troubadour serenading his lady amongst the hawthorn trees (also known as "May trees" and "Fairy trees") in May. Hawthorn tapestries left and right (William Morris).

The "Nature Introductions": Exordium & Reverdie

In connecting a previous musical essay series, "The Troubadours & The Beloved" to the present "Beltane/May Day" series, GS had discussed poet Ezra Pound's assertion that behind the troubadours was a secret, erato-mystic love cult based upon an ancient pagan fertility religion and quoted Pound: "... the birth of Provençal song hovers about the Pagan rites of May Day.”

Therefore, the GS would connect his current Beltane/May Day musical essay series back thematically to the troubadours, who celebrated in poetry/song the twin joys (joi) of spring and love for the months of April and May.

Concerning the troubadour love poems/songs with the theme of the Spring season, there are "nature introductions" known as exordium in the genre of reverdie ("re-greening") in troubadour poetry/song (usually only first stanza) linking of spring and love. The troubadours often used the exordium when springtime weather inspires and bird songs “teach” the poet to sing. The bird in many troubadour cansos serves as the poet’s “messenger,” who will carry his message to his beloved. Technically speaking, the reverdie specifies time of composition at the end of March and early April. Spring inspires love and song, and the poem’s position is a love plea. As one literary historian tells us: “The reverdie properly belongs to May-Day festivities." (There are some 35 examples of "nature introductions" one can find.)

The earliest extant example of the musical form of the alba (dawn song) is the song "Kalenda Maya" (or "Kalenda Maia:" "The Calends of May") written by the troubadour Raimbaut de Vaqueiras (c.1150–1207) to the melody of an estampida, a dance form played by French jongleurs. (The Romans called the first day of every month the calends, signifying the start of a new lunar phase.)

“On the first of May, gay the plumage of birds,

Song the day, loud the cuckoos.”

(From a 6th-century Celtic Welsh poem, "The Calends of May")

When the days are long in May,

I like a sweet song of birds from afar …

And neither song nor hawthorn flower,

Can please me more than winter’s ice....

~Jaufre Rudel (12th century)

It’s sweet when the breeze blows softly,

As April turns into May ….

Whiter she is than Helen was,

The loveliest flower of May ….

~Arnaut de Mareuil (12th century)

Through her who holds my heart in play;

So I prize not April or May,

For she blithely turns away ….

~Peire Vidal (12th century)

This love of ours it seems to be

Like a twig on a hawthorn tree

That on the tree trembles there ….

~Guillaume de Poitiers (12th century)

%204.png)

%204.png)

May, and among the miles of leafing,

blossoms storm out of the darkness —

windflowers and moccasin flowers. The bees

dive into them and I too, to gather

their spiritual honey. Mute and meek, yet theirs

is the deepest certainty that this existence too —

this sense of well-being, the flourishing

of the physical body — rides

near the hub of the miracle that everything

is a part of, is as good

as a poem or a prayer, can also make

luminous any dark place on earth.

-Mary Oliver

Thematic Images for Origins of Beltane / May Day:

Roman Floralia, Goddess Flora, Pagan Gods, & Festivals

.jpg)

.

Pan and Syrinx

.jpg)

.

Pan and Flora

The Roman Saturnalia, ancient precursor to May Day revelries

The Roman Bacchanalia, ancient precursor to May Day revelries

German Walpurgis Night, a precursor to May Day revelries

(It is celebrated on May Day Eve and dedicated to the Anglo-Saxon goddess of Spring,

Walpurga, who was later Christianized as St Walpurga and thus "Saint Walpurga's Eve.")

Thematic Images for Beltane Gods & Goddesses

Thematic Images for Beltane / May Day Characters & Themes

May Queen "Come up, come in with streamers! Come in with boughs of May!"

Beltane / May Day Maidens

Thematic Images for Beltane / May Day Dances

Peasant Dances of the May Feasts (15th c.)

Thematic Images for May Day Maypole Fairs & Vintage Magazine Covers

Thematic Images for the Beltane / May Day Greenwood

Celtic "Otherworld" of the Faerie (Sidhe)

Thematic Images for Beltane / May Day Mid-Spring Festival

Thematic Images for Beltane / May Love: Maypole Lovers, Handfast Lovers,

Bowers of Bliss, Greenwood Marriage, and Sacred Marriage

Memes for Beltane / May Day Lovers Under the Hawthorn Tree

%20meme.png)

.jpg)

Beltane / May Day Lovers Memes

%20meme.jpg)

Beltane / May Day Erotic Lovers

“The Merrie, Merrie Month of May” has always been a merry month for lovers, when the swift current of the erotic impulse courses through leaf and vein, and so it was also called “The Lusty Month of May.” In the British Isles, young men and maidens would go “a-maying” on the eve of May Day (Beltane), spending all night in the greenwood to return at day-break, “bringing in the May.” Thus, May Day was a special time for lovers and sexual union, and the maypole played a central part in this ritualized courtship and mating. The maypole, symbolic of male and female sexual energies, was profusely decorated with flowers. Youthful couples disappeared into the fields and forest—in their greenwood “bowers of bliss” (arbor cupiditatis)—to make love under the moon, returning to the village to dance around the maypole.

This all disturbed the sexually uptight Puritans to no end, as they saw these “bacchanals” as smacking of paganism. One morally outraged Puritan wrote that “men doe use commonly to runne into woodes in the night time, amongt maidens, to set bowes, in so muche, as I have hearde of tenne maidens whiche went to set May, and nine of them came home with childe.” Another Puritan complained that, of the girls who go into the woods, “not the least one of them comes home again a virgin.”

The Origin of Jonathan Coulton’s song “The First of May”

JoCo: “And the whole concept of a dirty rhyme that references the first of May is stolen from some kind of traditional dirty rhyme that people used to say. In the past. Honestly I’m not entirely sure where it originated, but my grandfather used to say it, and I have met other people who’s grandparents used to say it…. Anybody have some more definitive explanation?” Mike: “Well, according to at least one source of the arcane wit (‘Another Almanac of Words at Play’ by Willard R. Espy), it's an old English folk saying that originally went: ‘Hurray, hurray! the first of May! / Hedgerow tupping begins today!’ ‘Tupping’ is, apparently, a colorful expression to describe sheep copulation. It's a shame it fell out of use.” Ed: “I heard James Taylor speak this rhyme in concert. He was introducing his ‘First of May’ song and said he heard his dad say it to himself. The lyrics of his ‘First of May’ are based on the idea suggested by the rhyme.” JoCo: “Oh man, you mean I stole this idea from JAMES TAYLOR?” (Taken from JoCo’s blog.)

Beltane / May Day Sacred Marriage (Hierogamy)

The boughs put forth their tender buds, and “Love is Lord of all!”

He bowed his head. He stood so still,

They bowed their heads as well.

And softly from the organ-loft

The song began to swell.

Come up with blood-red streamers,

The reeds began the strain.

The vox humana pealed on high,

The Spring is risen again!

The vox angelica replied—

The shadows flee away!

Our house-beams were of cedar.

Come in, with boughs of May!

~ Alfred Noyes, "The Lord of Misrule"

Thematic Images for the Beltane "Fire Festival":

The Traditional Fire Rituals & The Fires of Love

BELTANE, the cross-quarter fire festival, is traditionally celebrated on the eve of May 1st. It's all about new life and the full re-kindling of the year after Winter. It's about the renewal of Spring; about maypoles, dancing, flowers and the bright greens that only appear at this time of year.

The Celtic high priests, the Druids, kindled the great “Bel-fires” on the tops of the nearest beacon hill. Old Irish “Beletene” means “bright fire.” Gaelic “Bealtaine” means the month of May. At sundown on the eve of Beltane, great bonfires were lit throughout the land to attract the power of the sun back to Earth. The practical purpose of these bonfires was purify and sanctify the community and their livestock in readiness for the new cycle of the year. In rural homes the kitchen fire which burned all year round was extinguished, and the community gathered at the Beltane blaze, carrying away burning sticks as they left, to ignite their blackened hearths from a common flame.

The Celtic word "Beltane" is also said to mean the fires of the proto-Celtic god Bel or Belenos. (The word “Bealtaine” originates from the Celtic God “Bel,” meaning “the bright one” and the Gaelic word “teine” meaning "fire." Together, these words make “Bright Fire,” or “Goodly Fire.” Thus, Beltane (or Bealtaine) is a “fire” festival.” It appears, then, that the ancient Celts called the first cross-quarter festival on their wheel of the year “Beltane,” from the ancient word for “bright fire,” which honored their god of solar light and fertility. Thus, Beltane is sometimes literally translated as “bright” or “brilliant fire,” and is supposed to refer to the bonfires lit on Beltane eve by a presiding Druid in honor of the god Belenos. On Beltane Eve the Druids and their people gathered on high hills with a view of the rising sun and built great bonfires. House fires were extinguished and relit from these hilltop bonfires. These “need-fires” (“tein-eigen”) served to welcome in the summer, to encourage the sun’s warming rays, and to walk between for purification. Those gathered on Beltane were encouraged to leap the flames in a dynamic gesture of the acceptance of the blessing of fertility, creativity, and good fortune. So people leaped the fires to show the exuberance of the season. These joyous leaps turned into ecstatic dancing around the bonfires.

However, there was another purpose for these Beltane fires. The fires of Beltane also represented the fires of passionate desire that flared up though the ground and brought fertility to the land and the people. Couples leaped over the fire together to pledge themselves to each other. Traditionally speaking, then, this was a “fire festival” especially for young lovers, who made it through the cold and scarce winter months. With summer approaching, they could feel the fires of love rising in their solar plexus. Thus, for today’s Neopagans, Beltane signifies the flowering of cosmic sexual energies and mystical union between the goddess and the horned god, a time to be at harmony with the environment.

Beltane Fire Goddesses

Beltane Bonfire

Beltane Bonfire Circle Gatherings

Beltane Bonfire Dancing

Beltane Bonfire Leaping

%20meme.png)

The choice is between partial incorporation and total incorporation (integration). Participation (playing a part) or fusion. Total incorporation, or fusion, is combustion in fire…. The one is united with the all, in a consuming fire…. The word consummation refers both to the burning world and the sacred marriage…. Learn to love the fire. The alchemical fire of transformation …. Love is all fire …. The truth concealed from the priest and revealed to the warrior: that this world always was and is and shall be ever-living fire. Revealed to the lover too: every lover is a warrior; love is all fire. ~N.O. Brown, Love’s Body

The Sacred Marriage (Hieros Gamos):

Then fire, make your body cold,

I'm going to give you mine to hold,

Saying this she climbed inside

To be his one, to be his only bride.

And deep into his fiery heart

He took the dust of Joan of Arc,

And high above the wedding guests

He hung the ashes of her wedding dress.

It was deep into his fiery heart

He took the dust of Joan of Arc,

And then she clearly understood

If he was fire, then she must be wood.

~Leonard Cohen, "Joan of Arc"

Beltane Wiccan Bonfire Ritual Ceremonies

.jpg)

May Queen at Beltane Fire Festival (Edinburgh, 2022)

.jpg)

Beltane Fire Festival (Edinburgh, 2022)

Thematic Images for Beltane / May Day Festivals

William Blake, "May-Day In London" (1784)

.jpg)

"May Morning" (c 1760). This painting by John Collet depicts a street scene with a mixed group of people including a chimney sweep, a hurdy-gurdy player and a milkmaid with her traditional May Morning garland, all figures traditionally associated with May Day.

The May Day Parade in Minneapolis is the largest and longest-running parade in the country. The last time it took place was Sunday May 5th (“True Beltane” date), 2019. The annual parade, hosted by “In the Heart of the Beast Theatre,” draws large crowds and showcases large puppets, floats, and entertainment by performers. The event also features a festival in Powderhorn Park and a "Tree of Life Ceremony" involving more than 300 performers. Each year's parade/festival has a theme, ranging from Spring and environmental topics to social topics like peace and racial justice—blending the spring May Day with the sociopolitical May Day. This all-inclusive type of commemoration has been termed the “Green Root” and the “Red Root” May Day traditions.

Thematic Images for May Day "World Turned Upside-Down"

.jpg)

"The Topsy Turvy World" (or "The Dutch Proverbs" Brueghel, 1559)

.jpg)

The Lord of Misrule

.jpg)

In the 16th century, with the advent of Protestantism, the Puritans viewed these Maypole celebrations as smacking of paganism, as immoral, and a form of idolatry. (This was during the years following the Civil War in England, when Oliver Cromwell and the Puritans controlled the country during the Interregnum, 1649-1660.) One form of celebrating, dancing round the maypole, was described as “heathenish vanity” generally demonstrating “superstition and wickedness.” Because of the “unseemly” behavior of these celebrations, the then Protestant King of both England and Wales, Edward VI, ordered that these Maypoles to be destroyed, such as the famous Cornhill Maypole of London. The Puritans were outraged at the licentiousness and general immorality that often accompanied the drinking and dancing, sometimes referring to these May Day revelries as “bacchanals.” (One Puritan Reverend lamented: “I could not suppress these Bacchanals.”) Thus, in 1644 legislation was passed to ban village maypoles throughout the country, and dancing did not return to village greens until the restoration of Charles II in 1660.

This act of outlawing the maypoles has been identified by “carnivalesque” historians today as “the repression of collective joy.” Throughout Northern Europe (and especially England), a series of laws were passed in order to curtail the erection of maypoles among the common people, which had a devastating effect on all forms of collective pleasure. “At some point, in town after town throughout the northern Christian world, the music stops. Carnival costumes are put away or sold; dramas that once engaged a town's entire population are canceled; festive rituals are forgotten or preserved only in tame and truncated form. The ecstatic possibility, which had first been driven from the sacred precincts of the church, was now harried from the streets and public squares.” (Barbara Ehrenreich)

However there was another motive behind this church and state backlash against maypoles other than the one of outraged morality—a political one. During this period, the maypole began to take on an increasingly political edge, with common people expressing their socio-political grievances by setting up maypoles. They ultimately wanted the inversion of the social hierarchy—“the world turned outside down”—on a permanent basis and not just played out in their May Day games (officiated by a “Lord of Misrule,” who increasingly was the impersonated outlaw-philanthropist Robin Hood, famously known for “stealing from the rich and giving to the poor”) for a few festive days. Of course, the church and state became greatly alarmed at such politicized May Day festivities. “From the sixteenth century on, the carnivalistic assault on authority seems to become less metaphorical and more physically menacing to the elites.... People again and again dressed up their rebellions in the trappings of carnival: masks, even full costumes, and almost always the music of bells, bagpipes, drums. Similarly, the maypole, around which so many traditional French and English festivities revolved, became a signal of defiance and a call to action.” (Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie) “In this context, we find the pagan maypole popping up again. Although traditional festivities had been largely vitiated or expunged by the Church at the end of the 18th century, rural people were still in the habit of announcing their political intentions by setting up a maypole. Such maypoles served a political purpose: to call to riotous assembly, a sort of visual alarm bell.” (Mona Ozouf)

Hence, what we have here is totally unique in the history of popular political agitation—the merging of “collective joy” with political activism, or collective pleasure and spontaneous uprising from below (which wouldn't be seen again until the mass demonstrations of the 1960s). Thus, the following account from one town in the south of France in July of 1791 can be seen as a good example of what was breaking out all over Europe. “It is reported that peasants attacked weathercocks and church pews—symbols of feudal and religious authority respectively: “both with some violence and in the effusion of their joy ... they set up maypoles in the public squares, surrounding them with all the destructive signs of the feudal monarchy.” (Mona Ozouf)

Yet, the conventional wisdom would have us believe that this kind of “carnivalesque revolt” was rare and merely coincidental; that for the most part the political agitators carried on without such carnivalesque trappings. However, this is totally mistaken: “It is in fact striking how frequently violent social clashes apparently ‘coincided’ with carnival … to call it a ‘coincidence’ of social revolt and carnival is deeply misleading, for … it was only in the late 18th and early 19th centuries—and then only in certain areas—that one can reasonably talk of popular politics dissociated from the carnivalesque at all.” (Peter Stallybrass and Allon White [My emphasis]) (Of course, the generation who came of age during the mass demonstrations beginning in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, with their ecstatic music and street theater, know better, even though they probably never recognized that their political events were “carnivalesque.”)

Thematic Images for International Workers May Day from Walter Crane

.jpg)

The figure in these three illustrations (by Walter Crane) representing the International Workers' celebration for May Day 1895 is actually a representation for Flora, the Roman goddess of spring and flowers, whose festival, Floralia, was celebrated in Rome during late April and early May. Because of the stark similarity of customs, cultural historians and folklorists believe that the Floralia festival is the prototype of the later European May Day festival. Hence, this is evidence for the GS's theory that the two separate May Day observances (the seasonal and the socio-political) stem from common historical roots—the "green root" and the "red root."

.jpg)

%201.png)

%204.jpg)

The above illustrations for the Worker's May Day are from the nineteenth-century artist, book illustrator, cartoonist, and craftsman Walter Crane. (Some images are modified.) If, like the Gypsy Scholar, you had intuited that the two seemingly separate May Day festivals—the seasonal, pagan May Day and the socio-political, worker's May Day—are really not separate at all, that they are more like two roots of one great historical Flower—a "green root" and a "red root," respectively—, but needed some substantial evidence for such an intuition, then Walter Crane is your man!

Crane was both an artist with pagan sensibilities of nature and a committed socialist (the GS would argue an anarcho-socialist), which meant that he had a foot in both worlds. Thus, these illustrations for May Day are prime examples of a socialist art grounded in an idyllic natural world, expressive of the (Romantic) mythic imagination. More to the point, the Workers' May Day these illustrations portray is not that of the standard Marxist variety of a demythologized and mechanized worldview but rather one presided over by a nature goddess from ancient times—Flora, the Roman Goddess of Flowers, whose festival, the Floralia, took place in late April and early May of the Julian calendar. (Folklorists believe that the origin of May Day as a seasonal festival is the Floralia.) Flora now appears in the illustration "A Garland For May Day 1895," pressed into service for the socialist cause. "Dedicated To The Workers," she is depicted as holding up her traditional garland of flowers, but now wears the Phrygian (red) bonnet (the long-time symbol of revolution, particularly associated with the French Revolution). Likewise in Crane's 1890 illustration (which he drew in 1889, after May 1 had been chosen as International Workers' Solidarity Day), "Labour's May Day: Dedicated To The Workers Of The World," with its theme of the "Solidarity of Labour," she also sports the Phrygian bonnet, but this time she is a winged figure with the word "Freedom" inscribed over her head. (She previously appeared as an angelic figure in Crane's 1885 painting "Freedom.") Here, she is holding banners with the words "Fraternity" and "Equality" on them. The five inhabited Continents are listed, each adjacent to the worker representing that Continent. Workers around the world have all laid their tools down to take a break from their labors and enjoy a simple circle dance in solidarity with each other and with Flora herself, and in celebration of the simple joy of being alive—just like the commoners ecstatically dancing around their maypoles on May Day or (Celtic) Beltane. (This is hardly the type of message put out by the official "scientific socialism" of Marxist artistic propaganda of the time!)

Of all these illustrations, "The Worker's Maypole" (first published in 1894 in the socialist journal Justice) is the one that most revealingly fuses together the two May Days. Here, Crane emphasizes the striking vitality of the modern Workers' May Day by connecting it with the maypole (the preeminent symbol of pagan vitality celebrated in the seasonal May Day—the same maypole that became politicized in the premodern period, serving as a "lightening rod" signal to the oppressed workers to rise up in "carnivalesque" rebellion) and the female form; in this case the May Queen. "The Worker's Maypole" declares "the cause of labour is the hope of the world." The May Queen, wearing the Phrygian bonnet, holds a banner emblazoned with the slogan "Socialization, Solidarity, Humanity." Women are represented by the May Queen at the top of the illustration, with her crown showing the legend "Freedom" with banners from her wings/arms reading "Fraternity" and "Equality". In the centre of the scene Crane's beflowered May Queen welcomes the toilers of the world and carries their banners high. Dancing workers (like those ecstatic maypole dancers of old) interweave ribbons labeled with specific industrial complaints, such as “Eight Hours” (the duration of the work day), "Employers’ Liability," and "No Starving Children, into those that evoke utopian ideals such as “Leisure for All and A Life Worth Living.” Set within an ogee of undulating vegetation, the illustration addresses itself to the viewer in terms of visual profusion. Lines curve and shape upward and downward, a graphic evocation of the joyful expressions of the workers. (What progressive writer Barbara Ehrenreich identifies as the essential element of the medieval and premodern May Day celebrations—"collective joy," which Western culture lost with the Puritan and capitalist repression of this festival.) In this visual celebration of cooperation, the graphic line itself weaves and dances. This, it seems to say, is indeed a life worth living. Here, Crane foregoes the standard socialist tools of satire, parody, and caricature in favor of idealism, in particular the evocation of a pastoral idyll that condemns the industrial present (in a similar way that rural commoners of the premodern period in England demonstrated their rejection of capitalist industrialization by setting up their maypoles and celebrating—at least, that is, before the Puritan authorities banned maypoles in 1644). With "The Worker's Maypole," then, the socialist artist has transcended the strict ideological position of Marxist socialism with his post-revolutionary imagery. Therefore, the GS would argue that Crane's offering for May Day of 1894, "The Worker's Maypole," brings together the English folk tradition of the May Day maypole and the demands of the international labour movement; in other words, Crane was the first, as a modern artist and political radical, to recognize and demonstrate the interconnection of the age-old, seasonal May Day and the nineteenth-century, socio-political May Day.

There is further evidence of Crane's artistic seasonal/pagan sensibilities concerning May Day. They can be seen in his lithograph illustrations for three children's books (part of his oeuvre of "flower books"): (1) The First of May: A Fairy Masque (1881), a story of fairies and flowers, as told and rendered by illustrations to poems written by Crane. (2) Flora's Feast: A Masque of Flowers (1889). That Flora was an important goddess figure for Crane in relation to May Day is also evidenced in two of his works: the painting "Flora" and the set of tiles entitled "Flora's Train." (3) Queen Summer, or, The tourney of the Lily & the Rose (1891). Also worthy of note here are two seasonal paintings, "The Coming of May" (1873), "Summer 1895," an illustration that combines May Day flowers and the workers' May Day, "Flowers For The Labour's May Day" (1898), another that combines the May Day theme of love with socialism, "A Posy For Mayday and A Poser For Britannia" (1910), and yet another along the same lines, "Her Message to Labour for May Day;" a goddess of flowers giving a "May Day" message of hope to the workers" in terms of the coming of the sun and spring. Finally, we can see Crane's seasonal/pagan sensibilities expressed most revealingly in two poems for May Day. The first is part of a sequence of illustrations for the months of the year ("The Procession of the Months"). This "May" illustration features a traditional poem for the season (with verses by Beatrice Crane). The second is a May Day poem addressed to workers, whose first stanza evokes the traditional mid-spring theme of the season:

"World Workers, whatever may bind ye, / This day let your work be undone: / Cast the clouds of the winter behind ye, / And come forth and be glad in the sun."

As much as the traditional socialists want to keep Crane's "floral fantasies" resolutely separated from his serious political cartoons (which he dubbed "cartoons for the cause"), the GS would argue that they are just as "political" (in their evocation of a utopian ideal society) as any typical socialist cause. Again (to reiterate the GS' take on Crane a little differently), the Socialist artist is also the Romantic artist.

The images below are taken from the Crane works listed as prime examples of his seasonal/pagan sensibilities concerning the May Day.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%201.jpg)

%202.jpg)

Crane's Socialist Allegory (1885)

.jpg)

May Day "Carnivalesque" comes to Socialism in 1895

(Angel of ) "Freedom" (Crane 1885)

.jpg)

Thematic Images for International Worker's May Day

Workers' May Day festivities

.jpg)

The Monopolist's May-Pole (Puck Magazine)

"... May Day has its origins ... stemmed from the pre-Christian holiday of Beltane, a celebration of rebirth and fertility."

This opening paragraph (on the meme) from the archives of the Industrial Workers of the World website is copied here as a great confirmation of the Gypsy Scholar's contention that the modern sociopolitical May Day has its roots in the ancient (pagan) Celtic Beltane or "May Day"), traditionally celebrated on May 1. It's even more significant that this great confirmation comes not from some secondary, non-political source but from the organization of the IWW itself, and is therefore beyond question. (This source was only discovered after the GS had finished this webpage and presented his musical essay series for "Beltane / May Day.") The GS' musical essay series for "Beltane / May Day" argued that its main purpose was to demonstrate that the seasonal pagan May Day ("Beltane") and the sociopolitical May Day holidays are far from representing two very different types of holidays with nothing in common (as most people have been led to believe), but rather are related holidays that share a common root—the "Green Root" and the "Red Root" traditions respectively (as the above maypole images indicate).

Anarchist Chicago Haymarket Affair May 4, 1886

The Knights of Labor, originally named the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor (abbreviated K of L), was a significant labor organization in the late 19th century, operating from 1869 to 1886. It was a secret society that later became public and is associated with the Haymarket Affair. The Knights of Labor was known for its inclusive membership, encompassing skilled, unskilled, and semi-skilled workers, as well as immigrants, African Americans, and women.

This song demonstrates the GS's argument that (a) the labor movement's choosing to date their modern worker's May Day on the ancient, seasonal May Day wasn't a mere coincidence and (b) the worker's fighting for the 8-hour day wanted leisure time "to feel the sunshine" and "smell the flowers (perhaps the flowers of the Roman goddess Flora, whose May festival is probably the origin of May Day);" i.e., the time for play and to commune with nature. Again, this is an instance of the unifying "Green Root" and "Red Root" traditions of May Day

The story behind this worker's song is that Lucy Parsons, widowed by Chicago's Haymarket police massacre, was born in Texas and became a famous anarchist activist and member of the Knights of Labor. She was partly Afro-American, partly Native American, and partly Hispanic. She set out to tell the world the true story of her husband, Albert Parsons, who was executed in 1887 following the Haymarket affair: "of one whose only crime was that he lived in advance of his time." She went to England and encouraged English workers to make May Day an international holiday for shortening the hours of work. Her friend, William Morris (Romantic poet, artist, and craftsman), wrote a poem in honor of Parsons called "May Day."

Regarding the essential connection between the supposedly separate May Day observances, the GS notices the poem's twin theme of dedication to the cause of the workers of the world and to the Earth. Thus, once again, what we have in this poem is another instance of the unifying "Green Root" and "Red Root" May Day traditions.

International Worker's May Day

International Worker's May Day Events

Thematic Images for the May Day "Bread & Roses" Strike

As the two images above especially show, the International Workers' May Day has always been associated with flowers (particularly the rose), which came from the Roman May Day festival of the Floralia, in honor the the goddess of flowers, Flora. Furthermore, this association of spring flowering and the day to commemorate the rights of workers is also evidenced in poem and song.

The political slogan of "Bread and Roses" originated from a 1911 speech given by women's suffragette Helen Todd, which contained the line "bread for all, and roses too." This inspired the poet, novelist, and editor James Oppenheim to turn it into a poem in honor of the women's suffrage movement. The poem was first published in The American Magazine in December 1911, with the attribution line "Bread for all, and Roses, too"—a slogan of the Women in the West suffragettes. (In terms of the Women's Suffrage Movement, it is significant here that although the slogan was turned into a poem by a man the original musical setting was by a woman; Caroline Kohlslaat in 1917. The first performance of Kohlsaat's song was at the River Forest Women's Club, where she was the chorus director. Kohlsaat's song eventually drifted to the picket line—in a nice feedback loop of art and life.) By the 1930s, the song was being extensively used by women, while they fed and supported the strikers on the picket line at the manufacturing plants.The song also migrated to the college campus. At some women's colleges, the song became part of their traditional song set. It became associated in popular culture (if not historical accuracy) with the famous successful women's textile workers strike in Lawrence Massachusetts in 1912, now often referred to as the "Bread and Roses Strike." The event of the political slogan being turned into a poem has significance in that it counterbalanced the habitual exclusivity of the economic bottom line in socialist messaging with the co-equal demand for the other side of life—the more intangible necessities of the soul for its nourishment. Thus, the political slogan pairing bread and roses, appealing for both fair wages and dignified conditions, found resonance as transcending "the sometimes tedious struggles for marginal economic advances" in the "light of labor struggles as based on striving for dignity and respect." (Robert J. S. Ross, 2013.)

"As we come marching, marching, unnumbered women dead / Go crying through our singing their ancient song of Bread; / Small art and love and beauty their trudging spirits knew / Yes, it is Bread we fight for—but we fight for Roses, too.”

Thus, for the GS, this song represents the twin themes of worker's rights and the right to the entire aesthetic dimension—especially music (that makes for "Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness")—, which is represented by the eternal "symbolic rose," the flower sacred to Venus-Aphrodite, goddess of love and beauty, whose Roman festival (like Flora's) also took place during the month of May.

In terms of continuation of the "Bread and Roses" song in popular culture, it had a big revival in the 1960s, after being published in Sing Out! Magazine in 1954. Mimi Farina, sister of Joan Baez and husband of the singer songwriter Richard Farina, composed a new musical setting in 1974. (She started an organization called "Bread And Roses Benefit Agency" in the same year, its mission being to bring music to places that are usually not exposed to it.) Her setting was recorded by many other well-known folk artists. Besides Joan Baez, the earliest among them was Judy Collins, who performed it in 1967.

_jp.jpg)

.jpg)

Thematic Images for the Roman Rosalia Festival

_.jpg)

Thematic Images for the Industrial Revolution's Factories:

William Blake's "Dark Satanic Mills"

Thematic Images for Factories as "Dark Satanic Mills"

Thematic Images for Factory Workers of the Industrial Revolution

Child Factory Workers

"The Factory Girl" Workers

.jpg)

_.png)

"Song of a Factory Girl"

by Marya Zaturensky

It's hard to breathe in a tenement hall,

So I ran to the little park,

As a lover runs from a crowded ball

To the moonlit dark.

I drank in clear air as one will

Who is doomed to die,

Wistfully watching from a hill

The unmarred sky.

And the great trees bowed in their gold and red

Till my heart caught flame;

And my soul, that I thought was crushed or dead,

Uttered a name.

I hadn't called the name of God

For a long time;

But it stirred in me as the seed in sod,

Or a broken rhyme.

Some Labor History: Factory Fires, the Industrial Revolution

and the Enclosure Acts

.jpg)

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, a nationwide series of strikes and riots, erupted in response to wage cuts and harsh working conditions in the railroad industry. The strike began on July 14th, 1877, in Martinsburg, West Virginia, and quickly spread across the country, impacting nearly every major railroad center. The unrest was fueled by workers' grievances and a lack of organized labor representation. Between July 21 and 22 in Pittsburgh, a major center of the Pennsylvania Railroad, troops were dispatched and fired on the workers. Some 40 people (including women and children) were killed in the ensuing riots; strikers burned the Union Depot and 38 other buildings at the yards. In addition, more than 120 locomotives and more than 1,200 rail cars were destroyed. Pittsburgh was the site of the most violence and physical damage of any city in the country during the Great Strike. Fresh troops arrived in the city on July 28, and within two days peace had been restored and the trains resumed.

March 25, 1911 marks the date of the tragic Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, which killed 146 garment workers, mostly young immigrant women. This disaster remains one of the deadliest workplace incidents in the U.S. The factory owners, Blanck and Harris, had notorious anti-worker policies. When the International Ladies Garment Workers Union led a strike in 1909 demanding higher pay and shorter and more predictable hours, Blanck and Harris’ company was one of the few manufacturers who resisted, hiring police as thugs to imprison the striking women, and paying off politicians to look the other way. Because of their fire-trap building and neglect of fire precautions, they were put on trial for manslaughter. The workers’ union organized a march on April 5 to protest the conditions that led to the fire; it was attended by 80,000 people. The tragedy eventually led to the development of a series of laws and regulations that better protected the safety of factory workers.

Thematic Images of Landscape Paintings During the Industrial Revolution

.jpg)

Dudley, Worcestershire (William Turner c. 1830)

.jpg)

Reflections on the Aire - on strike (John Grimshaw 1879)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

These two 1887 paintings by Vincent van Gogh, "The Factory at Asnières"and Factories at Asnières Seen from the Quai de Clichy," focus on the intersection of industry and the natural environment. Some interpret the painting as a representation of the industrialization of the French countryside, with the factories encroaching upon the natural landscape. The modern landscape depicts industrial growth as it takes over rural countrysides (a phenomenon called by some "banlieue" or "terrain vague"). A fence demarcates the line between the flowing rural field and emission-generating industrial complex. Van Gogh has used horizontal bands to deliberately depict the earthy hues and movement of the field in contrast to the solid, carefully drawn geometric shapes of the factories and chimneys. The painting seems to illustrate a line from one of van Gogh's favorite novels, L'Assommoir by Émile Zola: "a great forest of factory chimneys" filled the sky. Van Gogh was identified as one of the first, with other Impressionist and post-Impressionist painters, to depict industrial landscapes such as these paintings.

Industrial Revolution : The Romantic Reaction in Landscape Painting

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

The Industrial Revolution & Romantic Landscape Painting

The Industrial Revolution brought dramatic and long-lasting change in Northern Europe’s landscape and infrastructure during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. As innovations in steam power and the design of machinery developed and advanced, new factories, mines, railways and canals began to radically transform the landscape, manufacturing, and the way people lived and worked.The influence of the Industrial Revolution on all aspects of human life is difficult to overstate. The changes it brought about were massive, comparable in their force to only the Agricultural Revolution of the 17th century. Historically exceedingly perceptive of the social and political climate, artists of this period used their art not only to document the drastic changes suffered by the natural environment of countries such as England but also to criticize the values of the Industrial Revolution. One such group of were the Romantic artists.

Romanticism was an artistic and literary movement that began as a reaction to the Industrial Revolution. It originated in Europe in the late 18th century. Romanticism emphasized nature over mechanization and celebrated qualities like emotion, imagination, and the individual. Prominent Romantic poets included Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley, and Keats, who wrote poems expressing nature, spirituality, and criticism of industrialization. The Industrial Revolution helped create the Romantic movement by provoking emotional responses to its dominant forces. The most famous and influential of the Romantic landscape painters who lead the “Romantic Reaction” was J. M. W. Turner, known popularly as William Turner. (See above paintings, “Dudley, Worcestershire” and “Newcastle-on-Tyne”.)

Nature is one of the main themes that can be seen throughout Romantic poets, and The Enclosure Acts" was something of particular interest to some of the writers during this time period. “The Deserted Village” by Oliver Goldsmith is one poem who’s influence can be recognized as The Enclosure Acts. Because small farms were being destroyed throughout England in the re negotiation process of all of the land, some of the smaller villages were forced into changing how they lived because they had to adapt to the new land administered by the government. Romantic writers during this time used their skills of literature to express their emotions through their poetry.

The Industrial Revolution and the Romantic Movement: "The Romantic Reaction"

William Blake's "The Chimney Sweeper" and Child Labor in England

.jpg)

William Blake's two chimney sweeper poems were published in two parts; Songs of Innocence in 1789 and Songs of Experience in 1794. They are about the social evil of child labor. Specifically, children being forced to work as chimney sweepers in 18th-century England. The poem "The Chimney Sweeper" is set against the dark background of child labour that was prominent in England in the late 18th and 19th centuries. At the age of four and five, boys were sold to clean chimneys, due to their small size. These children were oppressed and had a diminutive existence that was socially accepted at the time. Children in this field of work were often unfed and poorly clothed. In most cases, these children died from either falling through the chimneys or from lung damage and other horrible diseases from breathing in the soot. In the earlier poem, a young chimney sweeper recounts a dream by one of his fellows, in which an angel rescues the boys from coffins and takes them to a sunny meadow; in the later poem, an apparently adult speaker encounters a child chimney sweeper abandoned in the snow while his parents are at church or possibly even suffered death where church is referring to being with God. The later poem works as a kind of update on the plight of the chimney sweeper—a young boy forced to do the horrible work of cleaning chimneys. Unlike in the first poem, this sweep can take no solace in organized religion—he is too experienced for that. He is so covered in black soot that he is barely recognizable, and explains to the reader that society has oppressed and exploited the natural joyfulness of his youth. The poem opens with Blake describing the chimney sweeper as "A little black thing among the snow" and the end of the poem condemns both Priest and King "who make up a heaven of our misery."

.png)

.jpg)

"Chimney sweep's boy in May Day dress" (1800s). Chimney sweepers parade and dance in ludicrous ribboned costumes in London on May 1 "Ramoneur en costume du 1er de Mai." (Handcoloured copperplate engraving after an illustration by William Alexander from J-B. Eyries' Paris, 1821. Jean-Baptiste Eyries was a French geographer, author and translator.)

William Blake's "Dark Satanic Mills"

Thematic Memes of Factory Songs and Information About the Songs

The term "Factory Girl" means "A Young Woman Working in a Factory." This is the most literal and historical meaning. It refers to a young woman employed in a factory, often in roles like textile production.

“The Factory Girl" is an old traditional folk song. It was collected from an oral tradition in the English language from both England and Ireland by Steve Roud around 1970. (Roud Folk Song Index Ballad Index K221. Roud's Index is a combination of the Broadside Index of printed sources before 1900 and a "field-recording index" compiled by Roud. It subsumes all the previous printed sources known to Francis James Child [the Child Ballads] and includes recordings from 1900 to 1975.) The first printed version of this popular broadside ballad was called “The Country Girl,” published in 1843. (The text here, however, is probably earlier than 1843, and is from the singing of Mrs. Cunningham of Annalong, Co. Durham. Verse 4 and the melody is from Robert Butcher of Downhill, Co. Derry.) The traditional folk song has been performed by various recording artists. (Since the early 1950s, there have been over 40 versions of the song recorded,

The “Factory Girl” folk song lyrics tell the story of a young man who meets a poor girl on her way to her job at a factory. She initially resists the singer's advances due to her class pride and ability to support herself. Endings of the folk song vary; in some, the two characters end up marrying, but in others, the girl ultimately rejects the suitor (thereby making the song one of unrequited love). In Rhiannon Giddens' 2015 version, the lyrics are rewritten so that the song ends with the collapse of the factory and death of the titular girl, in reference to the unsafe working conditions in many factories, particularly garment factories. Thus, this version becomes a social activist type of song. (Giddens' song was a response to the 2013 Dhaka garment factory collapse, and she has commented that she wanted to have the song apply to not only to the terrible working conditions of factories in the distant past and to also speak to the terrible working conditions in today's factories.)

“To me the factory bell in this song seems to toll the knell of the ‘maypole’ type of folk song.”

~ Sean O’Boyle

This quote from Sean O'Boyle (author of The Irish Song Tradition and teacher of Irish Music in Colaiste Bhride, Rann na Feirste) wonderfully confirms the GS' intuition that the "Factory Girl" folk song is a variation of the traditional May Day folk song, with the standard opening lyrics about roving out one May or summer's morning (songs played for the "Beltane / May Day" musical essays), which itself is of the genre of the Irish/British romantic folk ballad that originates with the Troubadours (songs about knights encountering shepherd girls whom they try to court), where the man roves out one fine spring or summer's day and encounters a young lass whom he tries to woo (if she rejects his advances, it's technically an "unrequited love" song).

The GS has commented upon this in one of his "Beltane / May Day" musical essays after playing the song, putting forth his notion that the song perfectly expresses both the "Green Root" and "Red Root" traditions of May Day (i.e., the ancient, seasonal May Day and the sociopolitical workers May Day respectively). By this the GS means that the "Factory Girl" folk song puts the sociopolitical factory worker's complaint (such as in the classic "Factory Girl's Song:" Come all you weary Factory girls, / I'll have you understand, / I'm going to leave the Factory / And return to my native land. / No more I'll have these tolling bells . . .") and puts it in the context of the genre of the romantic folk ballad (from which the standard May Day songs come). This is why the GS featured this song in the "Beltane / May Day" musical essay series as exemplifying his main argument; i.e., the two supposedly separate May Day observances are historically connected and, therefore, are actually one May Day observance incorporating the "Green Root" and "Red Root" traditions.

To read the history and background information of recordings of "The Factory Girl,"

including the various renditions of the song lyrics, click the link button below for the

English Folk and Other Good Music webpage.

To read the the Gypsy Scholar's in-depth comments about "The Factory Girl" folk song on the above webpage, click button below.

Music Videos of the Two Basic Factory Girl Folk Songs

"Factory Girl" is the traditional folk song sung by many recording artists, from Margaret Barry in 1952 to Bridget Hayden in 2025.

Although this traditional folk song version is entitled "Factory Girl," it's properly entitled "The Factory Girl's Song," which is different from the traditional one above. This folk song is technically distinguished as the "The Lowell Factory Girl" song. (See links above, about this song. There's also a more traditional version of this song by the Irish band Beoga that can be found online.)

Lady Maisery's album May Day contains—appropriately enough—

the song, "Factory Girl." A great confirmation for the GS deciding to have his "Beltane / May Day musical essay series contain the song.

Historical May Day Revolts

May Day 1968: The Student Revolt in France

1968 – No other year in the 20th century is given such a symbolic and iconic status, no other year is studded with myths, evokes associations, viewed with bias, and kindles emotions. A year in which protests, upheavals, and even revolutions took place in numerous countries around the globe: May 1968 stands for international youth and protest cultures in 56 countries, 22 European ones amongst them, but also for an art breaking out of its elitist ivory tower – parallel to this, masses of individuals in the Western world begin to strive for autonomy. It is first through the interaction between students, intellectuals, and artists that a cultural revolution capable of disrupting the authoritarian structures of societies in both East and West could take place. This world-wide wave of protest particularly occurred in May of that year. The protests are sometimes linked to similar movements that occurred around the same time world wide and inspired a generation of protest art in the form of songs, imaginative graffiti, posters, and slogans. Three of these protest movements (two in America and one in France) are worthy of note here.

Beginning in May 1968, a period of civil unrest occurred throughout France, lasting some seven weeks and punctuated by demonstrations, general strikes, as well as the occupation of universities and factories. The unrest and protests were initiated by anarchist university students and were later joined by trade-union workers from a number of factories. The revolt against the antiquated French educational system turned into a general youth rebellion that rocked Paris and nearly toppled the French government. At the height of events, which have since become known as "May 68," the economy of France came to a halt. The protests reached such a point that political leaders feared civil war or revolution; the national government briefly ceased to function after President Charles de Gaulle secretly fled France to Germany at one point. The May '68 student-led uprisings in Paris found expression in provocative and pithy signs and images. The most famous slogan of the student protesters was "All Power to the Imagination," which alluded to the essential power of the creative arts (an aesthetic power) in transforming socio-political reality.

In late April and early May of 1968, a series of protests led by the SDS at Columbia University in New York City were one among the numerous student demonstrations that occurred around the globe in that year. Protesting against the university's ties to the Vietnam War and its segregation policies, the students occupied and shut down the university, only to be violently quashed by the police. A second round of protesting occurred between May 17–22.

In 1968, San Francisco State embarked on a campus strike that lasted five months – the longest student strike in U.S. history. Led by the Black Student Union and Third World Liberation Front, the strike was a high point of student struggle in the revolutionary year of 1968. It was met by ferocious repression, but the strikers persevered and won the first College of Ethnic Studies in the U.S. In 1968, the 2-year-old Black Panther Party had raised Black consciousness and commitment to revolutionary change to a new high, and Blacks led the broad coalition behind the SF State strike. The student and faculty strike started on November 6, 1968 and lasted until March 21, 1969. However, the origin of the strike can be traced back May 2, 1967, when students orchestrated a sit-in at the office of the newly appointed president of the university in protest of the Selective Students Committee access to students' academic standing. Subsequent events, which included the suspension and firing of high profile educators of color, led to the formation of the coalition of ethnic student groups at San Francisco State College known as the "Third World Liberation Front."

May Day 1971 Anti-War Demonstrations in America

On 1 May 1971, some 35,000 protesters camped out in West Potomac Park near the Washington Monument park in Washington, D.C., in preparation for a demonstration against the Vietnam War. But the Nixon administration canceled the protester’s permit, and over the next few days U.S. Park Police, Washington Metropolitan Police, the D.C. National Guard, and federal troops clashed with, and dispersed, many of the protesters. This last and largest national anti-Vietnam War demonstration occurring that week has since become known as the “1971 May Day Protests.” This most influential protest has also been consigned to history as “the protest that changed America.”

“During one remarkable two week period — from April 19 to May 5, 1971 — more than a half-million citizens descended on the nation’s capital for the largest anti-Vietnam War rally, staging sit-ins that clogged entrances to several government agencies, camping out in a park where they put on a rock concert, and blocking streets and bridges that nearly shut down the city. Hundreds of war veterans joined the fray, lobbied Congress, engaged in civil disobedience at the Supreme Court and the Pentagon, performed mock guerrilla theater attacks on unsuspecting citizens on the city’s streets, and threw their war medals onto the Capitol steps.” (“How 1971’s Mayday actions rattled Nixon and helped keep Vietnam from becoming a forever war”)

Occupy May Day (USA)

May Day Anarchists

.

Thematic Images for May Day "Dancing in the Street"

Maypole Spiral-Dance

Dancing to fiddle in May Day

Country Mirth (Douce Ballads)

Anarchist Emma Goldman's dancing revolution

The following article supports the GS's contention (as articulated in his musical essay series, "Beltane / May Day") that (a) the roots of May Day for international workers lie in the seasonal, pagan festival of May Day and (b) the prototype the latter May Day can be found in the Roman Floralia.

"May 1 was a traditional Spring holiday across the northern hemisphere, with numerous rites and ceremonies taking place from Great Britain to Bulgaria. The very first record of May Day celebration appeared with Floralia, the festival of Flora, the Roman goddess of flowers, celebrated on April 27 during the Roman Republic era, and with the Walpurgis Night Celebrations of the Germanic countries. It is also associated with the Gaelic Beltane, most commonly held on April 30. The day was a traditional summer holiday in many European pagan cultures. While February 1 was the first day of spring, May 1 was the first day of summer; hence, the summer solstice on June 25 (now June 21) was Midsummer."

The following excellent essay, "The incomplete, true, authentic and wonderful history of May Day," by the Marxist labor historian Peter Linebaugh is extremely important, in that it supports the GS's overall argument in this musical essay series ("Beltane/May Day" A Holiday for Pagans & Workers"); i.e., that the two supposedly separate May Day observances, the seasonal pagan and the sociopolitical workers', are historically connected and therefore one great May Day observance with two unifying roots––the "Green" and the "Red" respectively. To quote the beginning of Linebaugh's essay (discovered midway through the musical essay series): "The truth of May Day is totally different. To the history of May Day there is a Green side and there is a Red side." He even goes on to make the same point the GS made about the origin of our modern May Day: "The origin of May Day is to be found in the Woodland Epoch of History. In Europe, as in Africa, people honored the woods in many ways. With the leafing of the trees in spring, people celebrated "the fructifying spirit of vegetation," to use the phrase of J.G. Frazer, the anthropologist. They did this in May, a month named after Maia, the mother of all the gods according to the ancient Greeks, giving birth even to Zeus."

In any case, Linebaugh's marvelous essay about the untold history of May Day is full of insightful connections regarding the "Red and Green" traditions of May Day. This is a must read as an extensive compliment to the GS's musical essay series––for this this no common Marxist historian, who is one part "Red" socialist historian and one part "Green" pagan folklorist!

.jpg)

%202.png)

.jpg)

_.jpg)

.jpg)