%20poster.png)

Thematic Images for the Orphic Essay-with-Soundtrack:

"Romantic Total Revolution:

The Sixties Second American Revolution"

Romantic Total Revolution:

The Aesthetic Political Vision of William Blake & Friedrich Schiller

.jpg)

Orc, the fiery archetypal figure of revolution.

(From Blake's America: A Prophecy, pl. 10)

.png)

"The Dance of Albion" or "The Glad Day"

William Blake's color engraving (ca. 1793) of the dancing youth Albion ("Eternal Man" or "Fallen Man") symbolizes not only a revolutionary "politically awakened England" but also "spiritual rebirth."

The Two European Romantic Visionaries for "Romantic Total Revolution:"

William Blake & Friedrich Schiller: Poet-Comrades In Arms

"Thus Arm in Arm with thee I dare defy my century into the lists." ~Friedrich Schiller

William Blake (11/28/1757 - 8/12/1827) in England and Friedrich Schiller 11/10/ 1759 - 5/9/1805) in Germany were contemporaries and had a common vision of the fundamental role of "Art" (and aesthetics in general) in society and its revolutionary potential for absolute human emancipation.

For Blake, the “Arts and Sciences of the Imagination” was the way to human emancipation. However, Blake's idea of “Art” was not just the restricted domain of aestheticism, but a whole mode of life; the life of the Imagination. “Art” is also the precise telling of truth. Consequently, great art for Blake is always revolutionary. He thus declares: “The Arts & Sciences are the Destruction of Tyrannies or Bad Governments.” (It should be noted here that this Romantic merging of art and politics, along with the Left’s theme of the “Social Responsibility of the Artist,” came to fruition with the 20th-century Frankfurt School of “Critical Theory" with Herbert Marcuse. I would describe this merger of politics and art “the aestheticization of politics and the politicalization of art.”)

Blake and Schiller were representative of the 18th- and 19th-century Romantic generation of poets, artists and writers who saw the French Revolution heralding of a "new age" of liberty and peace. Yet, with the dashing of this hope with its failure, they sought to reframe the political idea of revolution into a deeper ideal, which Schiller termed "total revolution." For Schiller, “a total revolution in man's whole way of feeling” was needed in order to facilitate human emancipation, and thus he advocated an “aesthetic way” to political freedom.

Anarchist Emma Goldman On the Concept of "Revolution" in Line with Friedrich Schiller’s Concept of “Total Revolution”

Emma Goldman: June 27, 1869 - May 14, 1940

Friedrich Schiller: November 10, 1759 - May 9, 1805

Emma Goldman, like Friedrich Schiller, believed that human beings, in modern

civilization, have never been free enough to develop and express their true nature.

Romantic Total Revolution:

The Political Vision of Herbert Marcuse

The Culture Heroes of the Sixties "Total Revolution"

Orpheus, Dionysus, Narcissus

Orpheus, along with Dionysus and Narcissus, are, according to Neo-Marxist (incorporates insights from other intellectual traditions like critical theory, psychoanalysis, and existentialism) political theorist Herbert Marcuse, the new culture-heroes of 1960s revolution. This adds to the Romantic vision of "total revolution." Marcuse holds that these mythological culture heroes that replace the old values based upon the (Freudian) reality principle with the alternative, repressed values of the pleasure principle —"play, enjoyment, sensuousness, beauty, contemplation, and spiritual liberation." "Thus," argues Marcuse, "the alternate interpretation is that the Orphic and Narcissistic Eros reveal a new reality, with an order of its own, governed by different principles. The Orphic Eros transforms being: he masters cruelty and death through liberation. His language is song, and his work is play. Narcissus’ life is that of beauty, and his existence is contemplation."

Marcuse's sense of political and cultural revolution is based not on the reality principle of realpolitik but instead on the ontological principles of "play, love, joy, and sensuousness." In contrast, then, to the Protestant Ethic, which was dedicated to the reality-principle, meaning human alienation from being and environment, Marcuse believed in values in service to the "pleasure principle," and called for the end of alienation and the realization of freedom: "And the true mode of freedom is, not the incessant activity of conquest, but its coming to rest in the transparent knowledge and gratification of being." What Marcuse called the "order of gratification," or what the Neo-Freudians call the "nirvana principle," was represented by the mythological culture heroes Orpheus, Dionysus, and Narcissus, who brought about "a redemption of pleasure." Again, Marcuse sought to replace the dominant reality principle ruling sociopolitical relations with the values of the pleasure principle, which are "play, enjoyment, sensuousness, beauty, contemplation, and spiritual liberation." Thus, according to Marcuse, Orpheus is "the voice which does not command but sings," and is "the gesture which offers and receives; the deed which is peace and ends the labor of conquest; the liberation from time which unites man with god, man with nature."

Given all this, in regards to an alternative take on traditional "revolution," the Gypsy Scholar would strongly suggest that Marcuse's idea of Orpheus as the culture hero with "the voice which does not command but sings" was embodied in the various Counterculture musicians of the 60s and 70s. And, of course, the other two accompanying returning culture heroes (or archetypes), Dionysus and Narcissus (or positive Narcissistic Eros) would represent the other primary aspects of the revolutionary countercultural era. Dionysus would (as both Marcuse and N.O. Brown, after Nietzsche, so famously called for) represent ecstatic sexual and political liberation; Narcissus (as Eros) would represent the entire "Peace and Love movement" (sometimes expressed as "free-love" and sometimes expressed as "make love not war"). Therefore, both Marcuse and Brown called for a new aesthetic sensibility, one that connected the erotic to the aesthetic mode of existence. The GS would also suggest that in terms of overcoming man's alienation from nature ("the liberation from time which unites man with god, man with nature") both Orpheus and Dionysus (the god who breaks all boundaries) represent the "back to nature" aspect of the 60s Counterculture.

Therefore, this is what Friedrich Schiller might identify as "total revolution." As a matter of fact, it was Marcuse who revived Schiller's Romantic notion of revolution in his sociopolitical theory. He drew heavily from Schiller's aesthetic philosophy, particularly in his concept of aesthetic education and its potential for social liberation. Marcuse viewed Schiller's ideas (i.e., "the aesthetic mode of existence") on play and beauty as crucial for understanding how art could challenge societal repression and foster a more liberated human consciousness. (See the Schiller section above and the accompanying link for his "quotations on art and aesthetics.")

Herbert Marcuse (1898 -1979) was a prominent member of the Frankfurt School (known for its critical theory, its attempt to synthesize Marxism and psychoanalysis, and showing the limitations of traditional Marxism). He became a key intellectual figure associated with the New Left movement of the 1960s. His work resonated deeply with young radicals who were seeking alternatives to the existing social and political order. Marcuse provided a theoretical framework that helped unify and inspire various leftist liberation movements of the era. Thus, his ideas significantly influenced the New Left and student movements of the 1960s. He has been remembered as one of the most influential social critical theorists inspiring the radical political movements in the 1960s and 1970s.

Orpheus

Narcissus

.jpg)

"The next generation needs to be told that the real fight is not the political fight, but to put an end to politics. From politics to meta-politics. From politics to poetry. Legislation is not politics, nor philosophy, but poetry. Poetry, art, is not an epiphenomenal reflection of some other (political, economic) realm which is the "real thing". . . . Poetry, art, imagination, the creator spirit is life itself; the real revolutionary power to change the world; to change the human body. . . . To begin to dance; who can tell the dancer from the dance; it is the impossible unity and union of everything."

~ N. O. Brown, Love's Body (1966)

This is the essence of why Marcuse and Brown parted visionary company, since to Marcuse (for all his daring ideas as a Neo-Marxist, such as sharing Brown's Dionysian vision of the ideal society) this was just going too far! (Marcuse called Love's Body "love mystified.") However, for the GS, Brown's take on "the real revolutionary power to change the world"—essentially the power of the "Imagination"—is keeping true to the Romantic vision.

It should be pointed out here that in Brown's seminal theoretical work, Life Against Death: The Psychoanalytical Meaning of History (1959) he basically makes the case that the answer to man's alienation and repression (or sublimation) starts with (what literary theorists call ) "The Romantic Reaction" and that psychoanalysis completes the "great romantic vision." References to the Romantic movement appear all over the text, for example: ". . . then once again it appears that psychoanalysis completes the romantic movement and is understood only if interpreted in that light. It is one of the great romantic visions, clearly formulated by Schiller and Herder as early at 1793, and still vital in the systems of Hegel and Marx . . . ." (p.86); " . . . we can also discern in the romantic reaction the entry of Dionysus into consciousness. It was Blake who said that the road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom . . . ." (p.176). The first quotation is highly significant to the GS' writings in this section, since Brown recognizes Schiller as helping to formulate "the great romantic vision[s]." This is the same Schiller whom the GS has identified (in his first "Romantic Total Revolution" musical essay) as the Romantic author of the “aesthetic way” of liberation, which culminates "total revolution"—the same Schiller whom Marcuse brought into 20th-century Critical Theory!

Romanticizing Revolution?

The Gypsy Scholar anticipates—just by the very title of his musical essay series: "Romantic Total Revolution" (based upon the literary idiom "Romantic Revolution")—that he will probably be accused of "romanticizing" the idea of revolution (the term "romanticizing" used in its negative sense to mean idealized or unrealistic; making it seem better or more appealing than it really is).

Therefore, the GS offers the following excerpts from a lecture series, "The Great Revolutions of Modern History," in support of his musical essay series.

"The Romantic Idealization of a Revolution," by Lynne Ann Hartnett, Villanova University

Revolutions, in the words of the British historian Christopher Hill, turn the world upside down. They challenge the fabric of society and people’s most basic assumptions. The radical energy of the 1960s and early 1970s signalled the spirit of a generation determined to transform the world. It defined an era.

Defining Societies, Cultures, and Nations

Revolutions offer the rare opportunity to see the hopes and priorities of the political underclass emerge from the shadow of powerful elites. We loudly hear the voices of those who are usually consigned to silence. We bear witness to the hopes and fears of women and men who might otherwise leave little, or no, historical record. By looking at revolutions, we find differences that help to define societies, cultures, and nations. But we also find commonalities of humanity and experience. Revolutions systemically alter the dynamic between the state, authorities, elites and the people; they attempt to fundamentally transform power relationships..... Revolutions are predicated on the idea that when the state is unresponsive, dismissive, or exploitative, the citizenry can exercise its agency through extra-legal means.

Romanticizing Revolutions

In revolutions, people refuse to be silent; they refuse to accept the status quo; they step outside traditional parameters to imagine new social, political, economic, and cultural structures. And they try to realize them.

People, therefore, are central characters in the drama of revolutions. However, some of the most turbulent and repressive revolutions are those in which ‘the people’ are simply invoked rather than directly involved.

It’s easy to get swept up in a romantic idealization of revolution. Revolutionaries want us to romanticize. In order to legitimize turning the world upside down, [note here the GS's recurring theme from his musical essay series on "May Day"] from revolutionary actors need to convince their peers and posterity that disorder, upheaval, bloodshed and even death—all of which come with revolution—are worth the sacrifice.

We see this romanticization of revolutions in a 19th-century painting by the French artist Eugène Delacroix depicting the revolution that overthrew King Charles X. "Liberty Leading the People" from 1830 literally paints revolution as an inspiring, sanctified event.

Liberty Leading the People (Delacroix 1830)

This is the paradigmatic painting of the idea of "Romantic Revolution."

Thematic Images for Romantic Total Revolution:

The Sixties Second American Revolution

.jpg)

The Second American Revolution

Successive waves of radical descent — from the nineteenth-century abolitionist movement to the popular uprisings of the Progressive Era to the labor militancy of the 1930s to the sweeping social and cultural transformation of the ‘60s and ‘70s that we are calling the second American Revolution — would keep the unfinished work of US democracy alive….

The civil rights movement — which won its greatest victories in the first half of the ‘60s — ignited the “Second American Revolution.” Inspired by civil rights and Black Power activism, a string of other liberation movements caught flame that decade and the next – including the Vietnam antiwar struggle, the United Farm Workers union, the American Indian Movement, women's liberation, and the gay and lesbian uprising. Together these upheavals — which were often linked by mutually supportive activists and shared goals — forged the nation’s most daring interpretation of freedom and justice since the first American Revolution.

This second revolution forced the country to change its assumptions about race, war and peace, gender, sexual orientation, reproductive rights, labor justice, consumer responsibility, and environmental protection. Almost all these movements grounded their claims at one time or another in the rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness — compelling America to be true to its stated ideals in the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights.

~David and Margaret Talbot (2021)

.png)

.jpg)

All Power To The Imagination

L'imagination au pouvoir ("Power to the imagination")

In May of 1968, something happened. It was a call to intellectual arms, as students in Paris participated in a full out strike that brought the country to a veritable standstill and brought the politics of emerging left wing Marxism (Neo-Marxism) into the mainstream. Inspired by countercultural, anti-imperialist, Marxist, and anarchist ideologies, students increasingly viewed themselves as part of a revolutionary struggle against capitalism and authoritarianism. A reaction against the French establishment, particularly the DeGaulle government, the protests began at Universities but soon spread to the streets and, in combination with labour unions, included almost two thirds of France’s working population. It brought the country to the brink of revolution. What started out as a simple, student lead discussion on social discrimination and the failings of bureaucracy was met with police action, and what was originally a simple conflict between students and University heads soon escalated to a full blown national strike, complete with riots in the streets across the country. The May 68 movement also contributed to the growth of feminist, environmentalist, and LGBTQ activism, and inspired radical thought in philosophy, media, and academia. In France, the movement's slogans and imagery remain touchstones of political and social discourse. May 1968 ("(Mai 68") became one of the most significant social uprisings in modern European history. (For the GS, this happening in May just confirms that the commemoration of May Day as both a seasonal and sociopolitical event ripples through history.)

This image is from Blake's America: A Prophecy (1793). It is an engraving of a figure Blake named "Orc," who is depicted here in the revolutionary fires of energy. Orc is Blake's fiery spirit of youthful rebellion, who attempts to overturn the established order of society and bring new life and energy. He represents both political and sexual revolution, and he taunts the controlling colonial power of the British. Blake was the great champion for the Imagination, who declared: "One power alone makes the Poet – Imagination The Divine Vision." Blake's view of the primacy of the Imagination (and his fellow Romantic's view, such as Coleridge, Wordsworth, and Shelley) was revived in the revolutionary era of the 1960s. It was then that the rebellious university students in Paris took to the streets in protest with the rallying cry, "All Power to the Imagination."

The background for meme is a painting entitled "The Protests"

%201.jpg)

The Counterculture as Sixties "Carnivalesque" Revolution

Counterculture Revolutions: From the 17th-Century to the 20th-Century

“Revolutions, according to British historian Christopher Hill, turn the world upside down. They challenge the fabric of society and people’s most basic assumptions. The radical energy of the 1960s and early 1970s signaled the spirit of a generation determined, with the help of countercultural music, to transform the world. Revolution then defined an era.” ~ Lynne Ann Hartnett

Christopher Hill's seminal book, The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During The English Revolution, is a classic study of such radical groups as the Diggers, the Ranters, and the Levellers. These English radicals wanted a fundamental overturning of society—a "turning the world upside down." (See the GS' Beltane/May Day and May Day Carnivalesque webpages for the sections, "The World Turned Upside Down" and (its subsection ) "The World Turned Upside Down & The Diggers" for images and supplemental information.)

Hill discusses how the Ranter ethic was diametrically opposed the ruling Protestant Ethic ethic in a section significantly entitled "A Counter-Culture?" (Significantly, that is, for the GS' section here on the 60s Counterculture! Indeed, what is described sounds a lot like the radical values of the Counterculture in rebelling against the status quo of Cold War America and its repressive puritanical values. Of course, the Countercultural group "The Diggers," who were a radical, community-based group in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district known for their unique blend of street theater, anarcho-direct action, and art happenings, were inspired by the original 17th-century English Diggers, or the "True Leveller" movement, which held private property to be a "sin." Of the Diggers, Hill writes: "The Diggers spoke on behalf of 'all the poor oppressed people of England and the whole world,' and hoped that the law of freedom would go from their country to all nations of the world." Thus, one suspects "A Counter-Culture?" is a rhetorical question with a wink! )

The GS will first quote from a previous chapter, which will serve as a segue to the relevant passages in "A Counter-Culture:" "The Ranters' emphasis on love is perhaps mainly a negative reaction to nascent capitalism, a cry for human brotherhood, freedom and unity against the divisive forces of a harsh ethic, [the Protestant Ethic] enforced by the harsh discipline of the market, as hitherto masterless men are drawn into the meshes of the harsh competitive society." In the same vein, Hill also refers to the Diggers and their rejection of money and private property, thus his term "Digger communism." Here one can discern the 17th-century origin of not only the 1960s Digger commune but also today's carnivalesque type of anarcho-socialist resistance to global capitalism. Something like this seems to be implied when Hill states that "the Diggers have something to say to the twentieth-century socialists" and "we can study with new sympathy the Diggers, the Ranters, and the many other daring thinkers who in the seventeenth century refused to bow down and worship it [the protestant ethic]."

"The Ranter ethic, as preached by Coppe and Clarkson, involved a real subversion of existing society and its values. The world exists for man, and all men are equal. There is no after-life: all that matters is here and now. Nothing is evil that does not harm our fellow men—as many of the existing insitutions of society do, and as the repressive humbug and hypocracy of the self-styled godly certainly do. 'Swearing i'th light, gloriously', and 'wanton kisses', may help to liberate us from the repressive ethic which our masters are trying to impose upon us—a regime in which property is more important than life, marriage than love, faith in a wicked God than the charity which the Christ in us teaches." (Abiezer Coppe "became the leader of the drinking, smoking, and swearing Ranters in 1649." He declared that his service was "perfect freedom and pure libertinism." Clarkson was an itinerant preacher turned Ranter, who believed that God was in all living things and in all matter. There was no external heven or hell and no such thing as sin to the pure. His political beliefs included that taxes rob the poor to pay the rich—a belief that can be substaniated today in July of 2025!)

What Hill writes next about the essence of the Ranter ethic is truly amazing, for it sounds exactly like what many writers, scholars, and intellectuals of the 1960s were writing about: the god Dionysus as a symbol for the sexual and psychic liberation heralded by the “New Sensibility.” The two most influential of these, after Nietzsche, were the Neo-Marxist Herbert Marcuse (Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry Into Freud, 1955) and classicist and Neo-Freudian N. O. Brown (Life Against Death: The Psychoanalytical Meaning of History, 1959). Both Marcuse and Brown (to a greater degree) sought to bring this mythic culture hero back from exile in order to lift bodily and psychic repression and apocalyptically transform society.

"It was a heroic effort to proclaim Dionysus in a world from which he was being driven, to reassert the freedom of the human body and of sexual relations against the mind-forged manacles which were being imposed." Hill then compares Clarkson to William Blake (the antinomian poet-prophet in the tradtion of these 17th-century "Antinomiams"): "We might very nearly be reading Blake. Clarkson looks forward to Blake again when he concludes that to the truly pure 'Devil is God, hell is heaven, sin holiness, damnation salvation: this and only this is the first resurrection.' The world is turned upside down."

Here, it is intriguing that Hill introduces Blake (beginning with "mind-forged manacles") into Clarkson's comments which end with citing the "resurrection." Intriguing because, like the Ranter Clarkson, Blake turned Christian doctrine upside down in his The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (cf. "hell is heaven"), proclaiming the body as holy. (It is noteworthy that in the last page of the previous chapter Hill concludes that after the unorthodox ideas of the radical sects fell into obscurity "Blake at least inherited ideas similar to those of the Ranters . . . .) Intriguing, also, because Brown in the final chapter of LAD, "The Resurrection of the Body," also introduces Blake (MHH) to vindicate his argument: ". . . the essence of the Romantic Reaction a revulsion against abstraction (in psychoanalytical terms, sublimation) in favor of the concrete sensual organism, the human body. 'Energy is the only life, and is from the Body . . . . Energy is Eternal Delight,' says Blake." Intriguing, finally, because it may be something more than just coincidence that Hill puts Ranterism in a context of Dionysian liberation form Protestant-Puritan repression and cites Blake in a chapter entitled "Life Against Death." Although Hill doesn't reference Brown's Life Against Death, his book came out in 1972, well after Brown's book had become a best seller. Thus, it seems very possible that Hill was well aware of it while he was working on his own book.)

There is another connection to make between Hill's discussion of these English radicals and the GS' musical essays and their accompanying webpages. Already mentioned was the Beltane/May Day webpage that goes with the musical essay series of the same name. There, a discussion of the politicalization of the May Day maypole (its role in inciting spontaneous popular insurrections) and its being outlawed by both the Puritan church and state was presented. In the context of that discussion, the tragic story of the English radical Thomas Morton and his "May-Pole at Merrymount" was included. Thus, it is worthy of note that Hill also mentions Morton and his dissenting community at Merrymount. Again, in the chapter "Life Against Death," he writes of the "Dionysian elements among the opposition to Puritanism" and how "Thomas Morton of Merrymount in New England in the 1620s encouraged servants to revolt against their masters, danced round a maypole and 'maintained (as it were) a school of atheism.'"

This alternative community of non-conformists didn't last long. Puritan Gov. William Bradford could no longer tolerate Morton and his unruly colony of "defiant heathens," who openly fraternized with the Native Americans of the region. (Morton’s book, provocatively entitled New English Canaan, spoke back to Puritan plans for America based in Exodus and The Old Testament—with the unblinkable human presence of “Canaanite” or Native American civilizations.) The last straw was when they erected their giant maypole. Thus, in 1628 Bradford dispatched the Plymouth militia under Myles Standish, who chopped down the Merrymount maypole and arrested Morton. He was hauled in chains before the governor, given a farcical trial in Plymouth, then marooned on the deserted Isles of Shoals off the coast of New Hampshire until an English ship could take him back home.)

(For images of Morton and Merrymount, along with detailed information, see the GS' Beltane/May Day webpage section, "The Maypole At Merrymount.")

The Psychedelic Counterculture as Sixties "Carnivalesque" Revolution

Ken Kesey and the bus Furthur

(According to Kesey, people don't understand that the name of the bus is actually a "philosophical concept.")

Romantic Revolution, "Beautiful Losers" & "Divine Losers"

At the end of the documentary, Magic Trip: Ken Kesey's Search for a Kool Place, Ken Kesey reflects on his experience about his famous 1964 psychedelic bus trip across America with the Merry Pranksters. TheGypsy Scholar is pleased as (acid) punch to quote Kesey here because it fits perfectly within the theme of his "Romantic Total Revolution & The Sixties Second American Revolution" musical essay series. To reiterate from the Introduction to the series.

Ordinarily, "Romantic Revolution" is a term used by literary critics to denote a radical change in cultural tastes during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in Europe; changes in poetry, letters, philosophy, and aesthetic canons of the period following the Enlightenment.... Therefore, in these dark times of crisis and despair, this musical essay attempts, by picking up the fallen standard of the historical lost cause of the Romantics—those "Beautiful Losers".... As the preeminent historian of the 60's, Theodore Roszak, observes: "To discuss Romanticism in this way is to take up one of the great lost causes in history." Yes, the GS discusses this lost cause of the Romantics—"The History of Them All."

Now, the term "Beautiful Losers," is the title of Leonard Cohen's 1966 surrealistic novel, Beautiful Losers. ( According to LC himself, was written under the influence of LSD under Hydra's blazing sun. Mr Kesey, does this pass your "Acid Test"?). Furthermore, Book I of the novel is entitled "The History of Them All." I mention this because it indicates that LC is alluding to the oft-quoted dictum: "History is written by the victors." Thus, the GS interprets the concept of "Beautiful Losers" as almost mythological when History is seen in these terms (a periodic pattern). And, of course, the term itself carries a sense that there's something wonderfully beautiful in the tragedy of their ultimate failure (whether it be the earth-based Titans losing out to the Olympian sky-gods, the Roman rebels under Spartacus defeated by the Roman Empire, the Irish nationals defeated in their Easter rebellion to the British Empire--or the failure of the young generation of the Sixties in changing the American Empire). This last Romantic lost cause is definitely connected to the novel. As Terry Goldie has written: "The novel reflects the zeitgeist of the 1960s." ("Producing Losers: Beautiful Losers," 2003.)

And, on that note, here's what Kesey had to say about all this (in synchronicity with the timing of this musical essay series):

"There's something about what we're doing is that we're meant to lose— every time. You make these for forays, you write these books, and you perform this music, but the big juggernaut of civilization continues, and you get kind of brushed to the side. But I think all through history there's been these kind of Divine Losers that just take a deep breath and go ahead, knowing that society's not going to understand it and not even caring, 'cause they’re having a good time.

The Psychedelic Counterculture Art

Psychedelic Counterculture "Carnivalesque" Festivals and Concerts

.jpg)

.jpg)

"A Gathering Of The Tribes For A Human Be-In" poster (1967)

"That psychedelic poster art played an enormous role in the hippie scene is undeniable, and aside from the incredible music associated with the movement, it’s the visual art that has left the most lasting impression. While many are familiar with the posters and handbills that announced acid rock concerts at San Francisco’s Fillmore Auditorium and Avalon Ballroom, those works in no way represent the total output of psychedelic artists. Posters were also an influential method of communicating the movement’s ethics, moral principles, and political actions. The new visual language and typography of psychedelic posters promoted everything from anti-materialism and spiritual values to community festivals and antiwar protests. A good example of this would be one of the rare posters in my collection, "A Gathering Of The Tribes," a split-screen serigraph printed in wild day-glow colors that celebrated Native Americans and their traditional way of life as an example for hippies to follow....

Nevertheless, the poster is an outstanding example of psychedelic art and how such works were flavored with social protest and a questioning aesthetic. This particular poster used a 1868 quote by the painter of early Native Americans, George Catlin, as he described his encounters with indigenous tribes. In typical psychedelic fashion, the poster’s typography was psychedelicized and woven into the overall design. The quote reads:

'I love the people who have always made me welcome to the best they had. I love the people who are honest without law—who have no jails and no poorhouse. I love a people who keep the commandments without ever having read them or heard them preached from the pulpit. I love a people who love their neighbors as they love themselves. I love a people who worship God without a bible for I believe God loves them also. I love a people who are free from religious animosities. I love a people who live and keep what is their own without lock and keys. I love a people who do the best they can—and oh how I love a people who do not live for the love of money.'

Posters like this not only celebrated Native Americans as heroes, they suggested templates for alternative lifestyles and put people in touch with history. It was no small matter for me to have discovered the life and works of George Catlin through this poster, and I’m certain the print touched the lives of many others in equally profound ways."

~ Mark Vallen, "Art For Change: Summer of Love - Take 2"

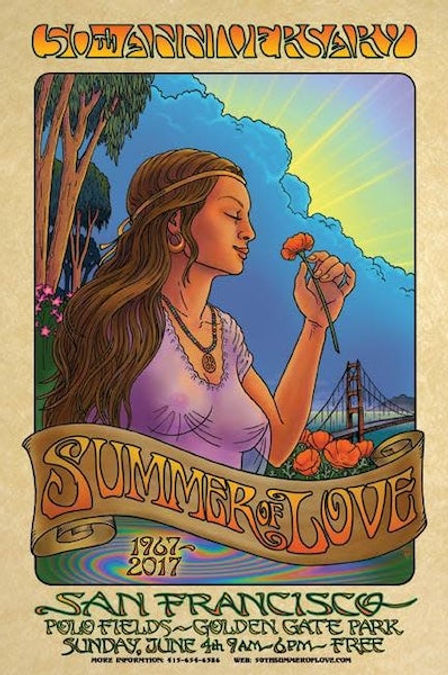

.png)

Original 1967 "Summer of Love" poster (Bob Schnepf)

The prelude to the "Summer of Love" was a celebration known as the "A Gathering Of The Tribes For A Human Be-In" at Golden Gate Park on January 14, 1967. It featured "All S. F. Rock Groups," which included The Grateful Dead, Big Brother & The Holding Company, Country Joe & The Fish, Quicksilver Messenger Service as well as Counterculture luminaries Timothy Leary, Allen Ginsberg, Dick Gregory and Jerry Rubin.

The poster features a psychedelic photo image of a mystic guru with a third eye. It was at this event that Timothy Leary voiced his motto, "turn on, tune in, drop out." This motto helped shape the entire hippie Counterculture, as it voiced the key ideas of 1960s rebellion. These ideas included questioning authority, dropping out of the system, communal living (especially living on the land), and political decentralization. The event that gathered together 30,000 people was announced by the Haight-Ashbury's hippie newspaper, the San Francisco Oracle: "A new concept of celebrations beneath the human underground must emerge, become conscious, and be shared, so a revolution can be formed with a renaissance of compassion, awareness, and love, and the revelation of unity for all mankind."

The "Summer of Love" was a social phenomenon that occurred during the summer (June) of 1967, when as many as 100,000 people, mostly young people sporting hippie fashions of dress and behavior, converged in San Francisco's neighborhood of Haight-Ashbury. It encompassed the music, hallucinogenic drugs, anti-war, and free love scene throughout the West Coast. Hippies, sometimes called "flower children," were an eclectic group. (The name derived from "hip," a term applied to the Beats of the 1950s, such as Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, who were generally considered to be the precursors of hippies. Although the hippie movement arose in part as opposition to U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, hippies were often not directly engaged in politics, as opposed to their activist counterparts known as "Yippies," the Youth International Party). Generally speaking, they rejected the conformist and materialist values of modern society and there was an emphasis on sharing and community. Many of them were suspicious of the government, rejected materialism and the consumerist values of mainstream American society. They generally opposed the Vietnam War and some were seriously interested in politics. However, most of them were more concerned with art (music, painting, poetry in particular) or spiritual and meditative practices. These came in search of transcendence—to “expand their minds” by means of free love, alternative religions, psychedelic rock music, and drugs (particularly hallucinogens, such as LSD). The musical denizens of “the Haight" included the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, and the Jefferson Airplane.

The reason the Gypsy Scholar has focused here on these two "Be-Ins" is because the term “Be-In” meant public gatherings—part music festivals, sometimes protests, often simply excuses for celebrations of life—that were an important part of the hippie Counterculture. As such, the GS sees these Be-Ins as the 20th-century successors of the May Day type festivals of the premodern period (as presented in his "Beltane/May Day" and "May Day Carnivalesque" musical essays series), as these summer celebrations of life increasingly began to take on a political edge and eventually became staging grounds for popular rebellion. Thus, the 60s Be-Ins were paradigmatic of the situational ambiguity involved in later gatherings of this type; i.e., were young people attending a political rally or a rock concert?

"The “Festival of Life" is a prime example of what the Gypsy Scholar sees as the unique carnivalesque phenomenon of a hybrid countercultural festival and a political protest rally.

It stands out as a prime example because it was held during the infamous "police riot" at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. This Counterculture celebration and protest festival in Lincoln Park was organized by the Youth International Party, whose members were called "Yippies." It was founded on Dec 31, 1967 as a radically youth-oriented and countercultural revolutionary offshoot of the free speech and anti-war movements of the 1960s, although their agenda and approach were quite different from traditional American political parties. (The Yippies put the "party" back in party politics.) Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, and others active in the movement to stop the war in Vietnam coined the name as a twist on “hippie,” a largely derisive term used at the time to describe young people who had embraced the Counterculture.

The Yippies were very savvy when it came to using the media to their advantage, staging theatrical events to highlight the failings of the dominant social order in America. One of the first Yippie events staged that August of 1968 was a Loop rally at which Pigasus, a live pig, was nominated for president. (Pegasus/"When pigs fly" was used as a symbolic leader.) This kind of outrageous political theater used by the Yippies is classical carnivalesque (a mode that "subverts and liberates the assumptions of the dominant style or atmosphere through humor, the grotesque, and chaos"). Thus, the carnivalesque political theater staged during the Democratic Convention was to nominate a 66-kg domestic pig for President of the United States.

The "Festival of Life" in Lincoln Park was organized in opposition to what Hoffman called the "convention of death" on the other side of town. The Yippies invited thousands of young people from across the country to the festival. Participants planned to camp overnight despite Mayor Richard J. Daley’s mandate to close the park at 11:00 p.m. each night. At 11:00 p.m. on August 25, 1968, police began clearing Lincoln Park. With batons and tear gas, they pushed the crowds of students and activists into the adjacent neighborhood. For the next four days, police and antiwar protesters clashed in Grant and Lincoln Parks and in the city’s streets.

To access the section "Carnivalesque Happenings in the Sixties and post-Sixties

Rock Music World" on the May Day Carnivalesque webpage, click button below.

.png)

The Counterculture Hippies and the Medieval Utopian Land of "Cockaigne"

"The Land of Cockaigne" (Bassano, 1606)

"The Land of Cockaigne" (or Cokaygne or Cokayne): a mythical utopian paradise on earth full of pleasures and epic leisure, where desires are instantly gratified. "The Land of Cockaigne" (in French, "Le Fabliau de Cocagne;" literally "land of plenty") grew in popularity as an escape from the harsh realities of life in the Middle Ages. It was a land of perfect harmony, where no one was poor, where food was in abundance, and where there were rivers of milk and beer. This European utopian dreamland was part of the repressed desires of the lower classes for a better life, free from the servitude and enforced hierarchies of the ruling class. "The Land of Cockaigne" can be understood as situated within the larger (late medieval and premodern) conception of the "topsy-turvy world," which manifested, during the common peoples' communal festivals, as what social historians term "rituals of social inversion" or, more popularly, "the world turned upside-down," where the traditional social hierarchies were inverted and serfs became kings; kings became serfs. In terms of the "Land of Cockaigne," it was, for example, "Where Whoever Works the Least Earns the Most."

The above images are the Gypsy Scholar's psychedelic hippie version of a countercultural "Land of Cockaigne."

This sixties hippie utopia was inspired by one of his favorite professors of English Literature, the prolific author of many books on Romantic literature (especially on Blake), Northrop Frye, who considered the countercultural hippies to be following the "outlawed and furtive social ideal known as the 'Land of the Cockaigne,' the fairyland where all desires can be instantly gratified."

(See illusrations of the Land of Cockaigne, along with accompanying information, on the GS' May Day Carnivalesque webpage, the subsection of "The World Turned Upside Down" section, "The Land of Cockaigne and Cuccagna: A Utopian Upside Down World.")

Christopher Hill's book, The World Turned Upside Down (referenced at length in the text-box at the beginning of this "The Counterculture as Sixties Carnivalesque Revolution" section) mentions the land of "Cokayne" in terms of the 17th-century revolutionary English Ranters, who sought to establish an alternative "Dionysian" society to replace the repressive order of Protestant-Puritan England. Hill cites the Ranter leader Abiezer Coppe, who declares that men should look for and hasten to "spiritual Canaan (the living Lord), which is a land of large liberty, the house of happiness, where, like the Lord's lily, they toil not but grow in the land flowing with sweet wine, milk and honey . . . without money." Hill then identifies this spiritual Canaan: "This is the land of Cokayne. of the tipsy topsy-turydom [the world turned upside down]. It was a revised version of the dream of the medieval peasant, as was the heaven on earth George Foster and Mary Cary had foreseen." (Foster was considered a Leveller prophet, who believed in the equality of all men and announced that the rich would share their wealth with the poor: "that the time was then that God would love all men, and the rich men should cast their gold and silver about in the streets." Cary was a English Civil War Presbyterian, prophesying and writing about church reform, poverty, equality for women, and who dreamed of building God's kingdom on earth.)

The Sixties Anarchist Revolution

.

"Misrule" is the byword for the medieval and premodern festivals of Carnivalesque "turning the world upside down"

Emma Goldman: The Great Anarchist of the American Early Twentieth Century

Emma Goldman (1869 – 1940) was an American anarchist, political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the 20th century. Born in Kovno, Lithuania on June 27, 1869, Goldman immigrated to the United States in 1885 and quickly became involved in the anarchist and labor movements. Goldman was called "the most dangerous woman in America" by J. Edgar Hoover because of her radical anarchist activism, which involved advocating for social revolution, workers' rights, and free speech through inflammatory speeches and writing, her opposition to World War I, and her support for controversial causes like birth control and free love further solidified her notorious reputation. Goldman was deported from the United States in December 1919 as a foreign-born radical, specifically an anarchist, under the 1918 Alien Act. After serving two years in prison for conspiring against the draft during World War I, she was deported along with 248 other individuals to Soviet Russia. Over the course of her life, Goldman’s activism and writing would inspire countless others to fight for social justice and radical change. She viewed the current labor system as inherently oppressive, turning workers into automatons and denying them the fruits of their labor and the joy of creative initiative. She believed true liberation for workers meant gaining economic and industrial freedom from exploitative bosses and a statist system, enabling work to be a source of joy, not a deadening compulsion. Her famous call to action was: "If they do not give you work, demand bread. If they deny you both, take bread. It is your sacred right!"

The Sixties and the Heretical Idea in Political Theory That

Popular Culture Can Be a Catalyst for Political Change

The artwork suggests the role of music in inspiring social change and unifying people. It also presents the idea that music can be a powerful tool for protest and social commentary.

Some books on Popular Culture

.jpg)

American Popular Culture

Global Popular Culture

Some info memes on Popular Culture

The Gypsy Scholar read the Declaration of Independence in his first musical essay of the series, which contains the outstanding words: "WE hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness — That to secure these Rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government . . . ." Since the GS emphasized the "Pursuit of Happiness" in connection with the lifestyle of the 1960s Counterculture, the following book was cited.

.jpg)