.jpg)

Carnival & Carnivalesque Artworks

Carnivalesque

.jpg)

Carnivalesque Scene

.jpg)

Carnival

.jpg)

Carnivalesque

Dream of a Carnival

.jpg)

Carnival at the Edge of Time

.jpg)

Carnival Fantasy

.jpg)

The Last Supper Inversion of the Sacred (Teraoka 2010)

.jpg)

The Cloisters – The Pyramid (Teraoka 2010–15)

These two paintings and those in gallery below (from early to modern art) illustrate Mikhail Bakhtin's concept of "carnivalesque" (“a literary mode that subverts and liberates the assumptions of the dominant style or atmosphere through humor and chaos”) as "grotesque realism" (as it is known in art history) consists of an inversion of the norms of social hierarchies, such as sacred and profane. "Grotesque realism" is a major element in the transgressive nature of carnivalesque. (For a detailed description of Bakhtin's idea of "grotesque realism" see link "A Note On Carnivalesque" at the beginning of this webpage.)

Thematic Images for Ancient Precursors to the Carnivalesque Carnival

.jpg)

Bacchanalia (1620)

.jpg)

Bacchanalia (1992)

Thematic Images for Early Carnival & Carnivalesque

(13th - 18th Centuries)

.jpg)

.png)

Many of the illustrations below are from a 16th-century manuscript detailing the phenomenon of Nuremberg's Schembart Carnival, (literally "bearded-mask" carnival). Beginning in 1449, the event was popular throughout the 15th century but was ended in 1539 due to the complaints of an influential preacher named Osiander who objected to his effigy being paraded on a float, depicting him playing backgammon surrounded by fools and devils. According to legend, the carnival had its roots in a dance (a "Zämertanz") which the butchers of Nuremberg were given permission to hold by the Emperor as a reward for their loyalty amid a trade guild rebellion. Over the years the event took on a more subversive tone, evolving to let others take part with elaborate costumes displayed and large ships on runners, known as "Hells", which were paraded through the streets. After its end, many richly illustrated manuscripts (known as "Schembartbücher") were made detailing the carnival's 90-year existence.

Take notice that the outlawing of this early carnivalesque-type carnival was because of the butchers of the trade guild, who at one time sided against a "trade guild rebellion" (yes, there were these "trade guild rebellions" as far back as the 15th century!), but eventually themselves got out of control and incurred the displeasure of a Protestant preacher. Again, as with the May Day carnivalesque carnivals, both church and state were responsible for their demise. Also, keep in mind that this is another instance exemplifying the historical fact that these 15th-century trade/craft guilds were the forerunners of the later 19th-century unions that instituted the May Day for the rights of international workers.

_jpgg.jpg)

Folies de Carnaval

A Carnival in the Middle Ages

"Folies de Carnaval" (Insanities of Carnival, Paris 18th c.) is a prime example of Bakhtin's concept of Carnivalesque: a transgressive mode that subverts and liberates the assumptions of the dominant style or atmosphere through humor and chaos. Thus, (a) carnival can represent a social institution that degrades or “uncrowns” the higher functions of thought, speech, and the soul by translating them into the grotesque body, which serves to renew society and the world; (b) carnival can be a moment when everything is permitted, when rank is abolished through social inversion of hierarchy (i.e., "The World Turned Upside Down") and everyone is equal.

The Carnival's Carnivalesque Scenes and Characters

Thematic Images for Carnival & Carnivalesque

(19th Century)

"On Pleasure Bent" (a Street Scene in Madrid during the Carnival by Robert Walker Macbeth, 1896). An example of the "collective pleasure" theme.

.png)

A Christian Evening in a Church (at Carnival time)

.jpg)

Pageant wagon for Shrove Monday (1837)

.jpg)

Thematic Images for Carnival & Carnivalesque

(20th and 21st Centuries)

Vintage American Carnival poster (early 20th c.)

.jpg)

Vintage American Carnival billboard (20th c.)

May Day Tree of Life Ceremony by Heart of the Beast Theater (Minneapolis)

.jpg)

Carnaval 2025 Mission District Festival (San Francisco)

.jpg)

Carnival of Cultures (Berlin)

"High Days and Holidays, A Good Excuse for a Feast" (Hook 1939)

.jpg)

"Inspiriacion" (Barrios)

Thematic Images for New Orleans Mardi Gras Carnival

.jpg)

"The Spirit of Mardi Gras"

Thematic Images of Carnival Posters

Thematic Images for King Carnival

.jpg)

Thematic Images for Carnival & Carnivalesque:

"The Battle between Carnival and Lent"

Battle between Carnival and Lent (Brueghel the Elder 1559)

Battle between Carnival and Lent (Brueghel the Elder 1559 [modernized])

Thematic Images for Carnivalistic Festivals & Fairs (Kermesse)

Flemish (Dutch) Renaissance painting of Antwerp (16th - 17th c.)

The Kermesse Of Saint George With The Dance Around The Maypole (Pieter Brueghel The Younger, 1616)

Thematic Images for Carnival & Carnivalesque Masquerades & Masks

.jpg)

.png)

Masks and Mysticism (Ensor, 1891)

Carnival & Carnivalesque Masquerades & Masks Artworks

.jpg)

Masquerade (Grigoriev, 1913)

.jpg)

The Venice Carnival (Edulesco, 2012)

.jpg)

Who is this Carnivalesque Radio Master of Ceremonies?

Thematic Images for Carnival & Carnivalesque "Feast of Fools"

Thematic Images for Carnivalesque "World Turned Upside-Down" or "Topsy-Turvey World" ("The Reverse World": Le Monde Renversé, Mundus Inversus, Il Mondo alla Riversa, El Mundo al Reves)

%202.jpg)

.jpg)

The Topsy Turvy World (Bruegel 1559)

.jpg)

The World Turned Upside Down (Steen c. 1660)

Some social historians theorize that what we know as “Carnival” today probably evolved out of the unruly May Day festivities. Here, the motive for “the repression of collective joy” (Ehrenreich) could very well be that the medieval and premodern May Day festivities often mocked the authorities with “rituals of inversion,” which turned the social order and its rules upside down. This is what is meant by “the transgressive nature of carnivalesque.” Thus, these transgressive festivities (which social historians call “carnivalesque”) increasingly gain a political edge after the Middle Ages, from the sixteenth century on, in what is known today as the early modern period. It is then that large numbers of people begin to use the masks and noises of their traditional festivities as a cover for armed rebellion. Thus, the Carnival theme of “the world turned upside down” meant that the underclass, the commoners, could not only take the advantage over their elite rulers of both church and state during the festivals of misrule but, more importantly, that they could imagine radical social change on a permanent basis and not just for a few festive hours.This is why social historians of this period refer to all such transgressive festivities, especially May Day, under the classification of “carnival” or, more properly, “carnivalesque.”

.jpg)

The World Turned Upside Down (Il Mondo alla Riversa, Nicolò Nelli c. 1552–79)

Below are a series of woodcuts from an 18th-century chapbook entitled The World Turned Upside Down or The Folly of Man, Exemplified in Twelve Comical Relations upon Uncommon Subjects. As well as the amusing woodcuts showing various reversals (many revolving around the inversion of animal and human relations) there is also included a poem on the topic.

The theme of “The World Upside Down” or “The Topsy-Turvey World” is found throughout Europe from classical times. It represents role reversals between men and women, men and animals, or adults and children. The most common image illustrating this theme is that of a man standing precariously on his head attended by jesters.

Odin Hanging from Yggdrasil

and Attaining Runic Wisdom

Jesus Upside down is Jester:

"The Laughing Jesus"

The Land of Cockaigne and Cuccagna: A Utopian Upside Down World

.jpg)

Cockaigne (or Cockayne) is a land of plenty in medieval myth; an imaginary utopia of extreme luxury and ease where pleasures are always immediately at hand and where the harshness of medieval peasant life does not exist. As described in popular stories and poems, there is no need to work, and food and drink are abundant. Like Hieronymus Bosch’s painting, The Garden of Earthly Delights, it is an edenic land of the fulfillment of earthly desires, a land full of pleasures and delights. Cockaigne grew in popularity as an escape from the harsh realities of life in the Middle Ages. Variations on the theme appeared across Europe full of new thrilling details under different names: “Cokaygne” (British Isles), “Cuccagna” (Italy), “Cocagne” (France), “Jauja” (Spain), “Schlaraffenlan” (Germany), and “Luilekkerland” (the Netherlands).

La terra di Cuccagna or The Land of Cockaigne (Niccolo Nelli c. 1564)

The Land of Cockaigne is actually a “world upside down,” in this case, too, the iconography alludes to the overturning of all traditional values. This topsy-turvy world was involved in the popular utopia of the Land of Cockaigne (or “Lubberland” or “The Land of Prester John”), where houses were thatched with pancakes, brooks ran with milk, there were roast pigs running about with knives conveniently stuck in their backs, and races where the last past the post was the winner. Thus, Cockaigne is a land of contraries, where all the restrictions of society are defied (e.g., abbots beaten by their monks), sexual liberty is exercised (e.g., nuns flipped over to show their bottoms), and food is plentiful (e.g., skies that rain milk). While there have been many different versions of Cockaigne appearing in literature throughout the ages, in general, the Land of Cockaigne was a medieval dream-world where the regular order things was flipped on its head.

.jpg)

Il Paese di Cuccagna - The Land of Plenty (Anon. 17th c. "Description of the Land of Cockaigne, Where Whoever Works the Least Earns the Most," 1606)

.jpg)

The concept of The Land of Cockaigne thrived during the 17th century as symbol of overabundance and excess. In Cockaigne, the poor would be rich, food and sex were freely available, and sloth was treasured and respected above all else. It was often portrayed as the perfect daydream of the common peasant, a place where the drudgery and struggle of medieval life was nowhere to be seen. Specifically, poems like “The Land of Cockaigne” (“Le Fabliau de Cocagne,” an Old French poem from the 13th century) offered a description of Cokaygne with houses made of food and rivers of milk and beer. Cockaigne, then, is the literal “land of milk and honey.” In the Land of Cockaigne there is also a Fountain of Youth.

Land of Cockaigne (Hendrik van der Putte, Amsterdam, c. 1761

In Italy, Cockaigne was called Cuccagna. (The country of Cuccagna is an ideal place, mentioned in many texts from every era, where well-being, abundance, and pleasure are within everyone's reach.) Developed in medieval times as a dream of escape shared by the lower classes, the myth of the country of Cuccagna—“a plebeian version of the aristocratic golden age,” as Piero Camporesi wrote—is based on the fantasy of a place where the abundance of food (mountains of cheese and rivers of wine), idleness, freedom and the pleasure of the senses, in the perspective of an upside-down world that does not admit hierarchies and where the vices sanctioned by official culture become virtues, such as idleness or laziness. Cuccagna offered a whole range of amenities: communal possessions, no animosity, free sex with ever-willing partners, and beautiful clothes.

.jpg)

Cucagna Nuova - The New Cucagna (Giuseppe Mitelli, 1703)

Like the theme of the “world upside down,” also the myth of the “Country of Cuccagna” is very old and is widely diffused in the popular tradition from the Middle Ages onwards.

In Italy, Cuccagna-inspired festivals, especially carnivals, were very popular and occurred regularly. They whisked impoverished Italians away from the hardships of daily life and launched them into the hedonistic world of Cockaigne. The celebrations featured elaborate temporary monuments decorated with food.

One of the popular artistic depictions of the Country of Cuccagna in relation to Carnavale was Il Trionfo de Carnavale nel paese de Cucagna (The Triumph of Carnival in the country of Cucagna ) by Niccolò Nelli.

Il Trionfo de Carnavale nel paese de Cucagna - The Triumph of Carnival in the country of Cucagna (Niccolò Nelli, c. 1552)

The Country of Cuccagna has many other utopian elements: the Cuccagna della Donne—a place of an ideal emancipation of women from her subordinate condition towards men—, representative of youth, madness and abundance as opposed to the old, lean and wise Lent, and the fantasy of the Upside Down World, where every social role is overturned with effect from time to time parodic, satirical and paradoxical, up to the more extreme inversion of species which places the animal in the place of man.

In this Italian Cockaigne there is also the fountain of youth, which men and women step into on one side to emerge at the other side as handsome youths and girls. But what would an Italian party be without wine? There are several mentions of cuccagnas featuring fountains of water accompanied by more luxurious fountains spouting wine.

Cuccagna posta sulla piazza del real palazzo - Cuccagna placed on the square of the royal palace (Vincenzo dal Re, 1749)

Naples was the eenter of the Cuccagna traditions. The city was very well-known for hosting the most elaborate cuccagna festivals in all of Italy. However, Cuccagnas were held in other Italian cities like Bologna, and even occasionally took place in France. The first Cuccagna displays were more like parade floats. Cuccagna celebrations originally looked a bit like Mardi Gras. Before the Italian royalty got into the cuccagna game, it was more of a public celebration usually timed around Lent. The structures looked more like parade floats which were built by the various food guilds of the city. The food guilds were groups of artisans like bakers and cheesemakers, and showing off their food.

Coccagnìa festival with exploding fireworks (Naples, c. 1728)

“But while this dream was certainly geared toward tempering the harsh realities of life at the time, it was also a form of protest. Cockaigne’s gourmands were opposed to the Church in particular, but also to the new secular authorities, who advocated abstinence and fasting, and condemned the deadly sin of gluttony. Le Fabliau de Cocagne describes a topsy-turvy world with carnival-type humour [i.e., carnivalesque] and the verses dedicated to the pleasures of eating are no exception….” (alimentarium.org)

“The Triumph of Carnival” attests to the popular saying:

“Cockaigne is a vision of life as one long Carnival, and Carnival a temporary Cockaigne” (with the same emphasis on eating and on reversals of the hierarchical order of things).

.jpg)

The Land of Cockaigne (Bruegel the Elder, 1567)

World Turned Upside Down & The Diggers

"The World Turned Upside Down."

Written by Leon Rosselson, the song "The World Turned Upside Down" honored the Diggers Commune of 1649. It is often thought that "The World Turned Upside Down" (not to be confused with the 17th century ballad of the same title), composed by Leon Rosselson in 1975, taken into the charts in 1985 by Billy Bragg and performed by several other artists, is a version of the "Diggers' Song". In May 2009 Leon Rosselson corrected this belief in the Guardian newspaper: “I wrote the song in 1974 …. It's the story of the Digger Commune of 1649 and their vision of the earth as 'a common treasury'. It's become a kind of anthem for various radical groups, particularly since Billy Bragg recorded it (1985), and is not adapted from any other song. The title is taken from Christopher Hill's book about the English Revolution.” (Hill, The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution, 1972) During the height of the Occupy Movement they often thought of this song and even sang it.

Thematic Images for Carnivalesque "Carnival of Resistance"

.jpg)

Extinction Rebellion Carnival of Corruption & Protest (Trafalgar Square, UK 2020)

Thematic Images for Carnivalesque In Our Time

Adbusters is a global collective of poets, punks and philosophers implementing radical design and media strategies to shake up complacent consumerist culture. We're aiming at the stale systems suffocating society: the power-hungry forces that leave people and the environment in disarray; the toxic capitalism that creeps into our bodies and imaginations.

(Image on the left: "Carnival of Anarchy.")

In traditional European popular culture, the most important kind of setting was that of the communal festival. The example par excellence of the European festival is Carnival. The term “carnivalesque” is a radical approach to carnival. It is used by social historians of the late medieval and early modern periods to denote art, festivals, or other activities that convey a sense of copiousness and social transgression from ancient times to the present day. The term owes much to the influence of the late Russian philosopher and literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin (1895 to 1975), whose exuberant descriptions of the festive life of the Middle Ages (based upon the writings of Rabelais) have led social historians to explore how popular culture might work as a force for political change.

Carnivalesque Rebellion & the Joy of Resistance; the Joy of "Total Revolution"

Schiller wrote a poem called “Ode To Joy.” (It is significant that it provided the inspiration for Beethoven’s famous Ninth Symphony and the lyrics to the choral portion of that work.) This ode extols joy as a divine spark—the spark from the Goddess of Joy—that unites all people as brothers and sisters. It calls for compassion, forgiveness, and a shared celebration of life. “Ode to Joy” is seen as a powerful expression of revolutionary and universalist sentiments, promoting peace and human connection during a time of political and social upheaval.

Schiller longs to merge state and society in a truly human community, but this alternative community must be based upon a “joyous aesthetic character.” For Schiller, “a total revolution in man’s whole way of feeling” was needed in order to facilitate human emancipation, and thus he advocated an “aesthetic way” to political freedom, which would merge state and society in a truly human community. In the fully human community, through total revolution, our freedom would become the means by which we establish internal and external harmony through a “joyous aesthetic character.” This “joyous aesthetic character,” according to Schiller, should accompany acts of moral freedom. Likewise, a “total revolution” in human character brought about by an “aesthetic education” should lead to the realization of the fully human community that follows from the realization of human freedom.

Herbert Marcuse revived Schiller’s thesis of “joy” and “play” in the 20th century. Thus, Marcuse’s sense of revolution is based on the ontological and epistemological principles of joy, play, love, and sensuousness

Herbert Marcuse brings back premodern Carnivalesque (with its "Collective Joy") in the guise of Neo-Marxist political theory.

Marcuse’s sense of political and cultural revolution is based not on the “reality principle” of realpolitik but instead on the ontological principles of play, love, joy, and sensuousness. In contrast, then, to the Protestant ethic, which was dedicated to the reality-principle, meaning human alienation from being and environment, Marcuse believed in values in service to the “pleasure-principle,” and called for the end of alienation and the realization of freedom: “And the true mode of freedom is, not the incessant activity of conquest, but its coming to rest in the transparent knowledge and gratification of being.” What Marcuse called the “order of gratification,” or what the neo-Freudians called the “nirvana principle,” was represented by the mythological culture heroes Orpheus, Dionysus, and Narcissus, who brought about “a redemption of pleasure.” Marcuse sought to replace the dominant reality-principle ruling socio-political relations with the values of the pleasure-principle, which are play, enjoyment, sensuousness, beauty, contemplation, and spiritual liberation. Thus "the voice which does not command but sings" is "the gesture which offers and receives; the deed which is peace and ends the labor of conquest; the liberation from time which unites man with god, man with nature.”

.jpg)

.jpg)

Carnivalesque Happenings in the Sixties and post-Sixties Rock Music World

The following images are examples of another facet of carnivalesque discussed in the GS' musical essays on carnivalesque: the propensity low, popular culture has as

a catalyst for political change.

Carnivalesque Music Festivals, Rock Concert Carnivals, Rock Raves, Rock Concert Tours

The Beatles Carnivalesque "Carnival of Light" & "Carnival of Light Rave"

(or "A Million Volt Rave")

"Carnival of Light" is the name given to an experimental piece of music Paul McCartney was commissioned to produce for a Carnival of Light Rave (a rave featuring music and light show), billed as A Million Volt Light and Sound Rave, which was held over two nights at the Roundhouse theatre on January 28th and again on February 4th, 1967. It was basically an art festival organized by BEV (the design firm Binder, Edwards & Vaughan) as a showcase for electronic music and light shows. It was held at the Roundhouse Theatre in Chalk Farm, north London. Posters for the event promised "music composed by Paul McCartney and Unit Delta Plus." This "avant-garde" recording within the "Stockhausen/John Cage bracket" (as McCartney has identified it) has been recognized as a precursor to John Lennon's "Revolution 9," recorded 18 months before that song. (McCartney likened the track to Harrison’s forays into Indian music with the Beatles and said he had recently renewed his interest in such experimental work. The sound engineer for the session, Geoff Emerick, wrote that Lennon's "Barcelona" yell and other "bits and pieces" from the "Carnival of Light" session were later recycled for "Revolution 9," a sound collage Lennon recorded with Yoko Ono in June 1968. Music journalist Steve Turner says that as a "musical freak-out" by the four Beatles, "Carnival of Light" "wasn't so much 'composed' by Paul as initiated by him." McCartney biographer Barry Miles suggests that the piece most resembles 'The Return of the Son of Monster Magnet'" from the Mothers of Invention's Freak Out!, an album that he had given to McCartney in 1966 and which resounded with the latter’s initial ideas for Sgt. Pepper. ) The Beatles recorded the new piece for BEV on 5 January 1967, early in the sessions for the album that became Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Since its only public airing in 1967, the nearly 14 minute recording has not surfaced on bootleg nor official Beatles release. (Music journalist Michael Gallucci has described "Carnival of Light" as "the holy grail of lost Beatles recordings.") The reason for it remaining unreleased is complex, but comes down to two factors: (1) In 1996, McCartney attempted to include "Carnival of Light" on the Beatles' compilation album Anthology 2, but was vetoed by Harrison, Starr, and Ono on the grounds that the track was never intended for a Beatles release. (2) From its inception, George Martin himself called "Carnival of Light" "ridiculous" and unworthy of release in the Anthology CDs. This harsh judgment was basically echoed by top music critics, such as Barry Miles, who dismissed it as "really dreadful" and concluded that "It doesn’t bear being released. It’s just masses of echo … It was the same thing that everybody was doing at home." In Ian MacDonald’s opinion, "the Beatles merely bashed about at the same time, overdubbing without much thought, and relying on the Instant Art effects of tape-echo to produce something suitably 'far out'." According to McCartney biographer Ian Peel, those who heard the sound collage recording at the "Carnival of Light" show were "comprehensively underwhelmed."

Carnivalesque Rock Carnival Concert Tours

Dylan's Carnivalesque "Rolling Thunder Revue Concert Tour" (1975)

When the GS first watched Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by director Martin Scorsese (2019), he thought the original 1976 tour fit the classification for "carnivalesque" that he'd been discussing in his May Day musical essays. However, solid verification of this didn't come until he found the above comments from reviewers.

The Festival Express or The Trans Continental Pop Festival (1970)

“The Trans Continental Pop Festival” tour began in Toronto, Canada at the CNE Grandstand and included the performers The Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, The Band, Traffic, Ten Years After, Delaney & Bonnie, Mountain, and Buddy Guy.

The music festival was staged in three Canadian cities: Toronto, Winnipeg and Calgary, during the summer of 1970. Rather than flying into each city, the musicians traveled by chartered Canadian National Railroad train, in a total of 14 cars. The train journey between cities ultimately became a combination of non-stop jam sessions and partying fueled by alcohol. Although the tour was a financial failure, it produced many notable performances, including some of the final performances by Janis Joplin, who would die about three months after the end of the tour. In the film, Mickey Hart of the Grateful Dead said, “Woodstock was a treat for the audience, but the train was a treat for the performers.” Jerry Garcia later said that what he remembers most about the tour is being “so blisteringly drunk”.

A documentary about the tour, “The Festival Express,” came out in 2003. The highlight of the tour documentary is a drunken jam session featuring The Band’s Rick Danko, the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir, New Riders of the Purple Sage’s John Dawson as well as Janis Joplin.

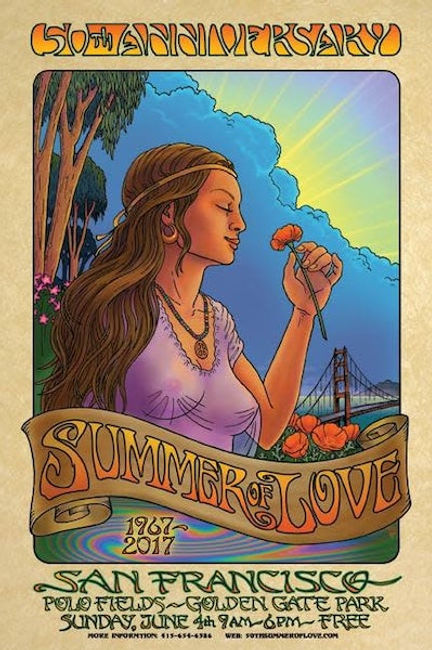

Some Carnivalesque Rock Posters, Album Covers, & Rock Artworks

.jpg)

The GS' argument in the third installment of the musical essays series “May Day Carnivalesque” is that the phenomenon of the carnival/carnivalesque festival from the medieval and premodern periods was revived with the 1960s Counterculture, where there was a blurring of the lines between rock festivals (specifically, musical Be-Ins, such as the “Summer of Love,” and “Woodstock”), or rock carnivals, and political demonstrations or rallies. In other words, there was the incorporation of music, dance, street theater, and performance art into political demonstrations and rallies—to the extent that a participant could justifiably ask themselves: “Is this a political demonstration, or is it a rock concert?” Therefore, to bring this idea of carnivalesque forward to our time, the above prime examples are of the phenomenon of carnivalesque happenings during the ’60s, ’70s, and to the present. These examples do not necessarily represent carnivalesque in toto, but they all nevertheless are a type of “carnival” and at least have strong carnivalesque elements about them, such as turning the world upside down (through flaunting authority, transgressive behavior, exhibiting ecstatic joy) and the painted face and masking. Again, they are examples of an important aspect of carnivalesque discussed in the musical essays; i.e., the propensity low, popular culture has as a catalyst for political change.

Psychedelic carnivalesque carnival

Psychedelic carnivalesque carnival (grotesque)

Psychedelic carnivalesque carnival (grotesque)

Cultural Activism: A set of creative practices and activities which challenge dominant interpretations and constructions of the world while presenting alternative socio-political and spatial imaginaries (“heterotopias:” cultural, institutional and discursive spaces that are somehow other and transgressive: disturbing, incompatible, contradictory, or transforming) in ways which challenge traditional relationships between art, politics, participation, and spectatorship.

Thematic Images for Carnivalesque Carnival "Dancing in the Street"

.png)

.jpg)

The Peasant Dance (Bruegel the Elder)

Village Street With Peasants Dancing (Bruegel the Younger)

.png)

Wedding Dance (detail -Bruegel the Elder)

.jpg)

"Street Dancers"

Thematic Images for Santa Cruz's Dancing in the Street Week

Thematic Images for Dancing in the Street Protests

.jpg)

.jpg)

Celebrate Freedom (Brown)

Street Dance (Tones)

Street Dance

.jpg)

Street Dance (Naylor)

Thematic Memes for Dancing in the Street

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20meme.jpg)