Father Time & Baby New Year

On the first of January, the Romans sent New Year gifts to each other, which were supposed to bring good luck throughout the year. On what is now the Christian "Epiphany" (January 6), Dionysus, the ancient Greek god of ecstasy and the "age-old ram," was born. The baby Dionysus, crowned with ivy and riding a ram, jumps over the threshold into our reality and toasts the world. This baby Dionysus may be one of early models for the image of the New Year babe we know today. The Church father Cement of Alexandria (140-215 CE) wrote that Dionysus's birthday was on January 6 and associated it with the birth of Jesus: "The birth of God happened with a lot of Dionysian wonders, such as the changing of water into wine." On the same day, the Christian feast of Epiphany celebrates the event in which Jesus changed water into wine at the wedding at Cana.

"Baby New Year has roots in the Greek god Dionysus, the god of fertility, wine (intoxication), festivity, and revelry. Dionysus was commonly depicted as a baby that is born at the end of our modern calendar year. During the age of Plato and Socrates, it was customary for Greeks to usher in the New Year with celebrations honoring Dionysus. One of their traditions was placing an infant in a winnowing basket and hoisting the child skyward to represent the rebirth of Dionysus."

For more info on the infant Dionysus and the New Year, click here

Father Time and New Year's Babe

Silenus with infant Dionysus (Roman copy after Greek original by Lysippos, 2nd century CE; Piero di Cosimo, ca. 1500)

Janus, the "God of Beginnings," with one face looking backward and one looking forward, serves as an image of the paradoxical theme for the New Year musical essay: in order to move forward, one must go backward. In other words, one must go "way, way back" in time to the mythic "the time of the beginning" (illo temore ab origine) in order to begin again in rebirth.

"To cure the work of Time it is necessary to go back and find the beginning of the World." ~ Mircea Eliade

Thematic Images for the Ancient New Year Ritual

%20festival.jpg)

Babylonian New Year Akitu festival

Assyrian New Year Akitu festival

Babylonian New Year Akitu festival

Babylonian New Year Akitu festival

For the ancient Babylonians, when their creation myth was recited over the New Year period, the creation of cosmos out of chaos actually happened all over again. First, the world fell back into chaos, as symbolized by, for example, chaotic behavior such as orgies. Then, through the ritual reenactment, the hero-god Marduk slew the chaos monster Tiamat and created the cosmos out of her body. As part of all this, time, seen as profane by the end of the old year, was abolished, then recreated as sacred once more.

Mesopotamian Ishtar (Inanna) New Year ritual

Thematic Images for Modern New Year Celebrations Around the World

Chinese New Year mandala

Ded Moroz, translated to (Grand)Father Frost, or Old Man Frost, is a legendary Slavic character that makes his rounds every New Year’s Eve. Along with his companion, Snegurochka, he brings delight to children as the two provide the little ones with gifts.

Many Native American tribes celebrate the New Year with dances as part of their great Winter Solstice ceremonies. For them, the New Year traditionally falls on the Winter Solstice day. This commemoration parallels the universal observance of the Winter Solstice by ancient indigenous European peoples (as discussed in the GS’s previous Winter Solstice season musical essays).

For detailed information on Native American New Year Commemorations, click here

Memes of New Year Celebrations for Calendars Around the World

Egyptian ancient calendar for today

In order to understand how the Western world came to celebrate the New Year on January 1, it may be useful to summarize the calendrical history of this date with some basic facts about the lunar and solar calendars of the ancient Sumerians, Egyptians, Hebrews, Greeks, and Romans.

For a brief history of the dating for the New Year, click here

The Gypsy Scholar presents:

The Argument-in-Song Behind the Orphic Essay-with-Soundtrack series,

“The New Year & Rebirth In Archaic Myth & Ritual”

According to Prof. Mircea Eliade, archaic and traditional societies had a profound need to regenerate themselves periodically through the annulment of profane time and enter into “mythic time” (the time of the gods, heroes, and ancestors). Archaic and traditional peoples periodically sought, through ritual “archetypes and repetition,” to abolish profane time and thus regenerate the sacred “time of the beginning” (in illo tempore, ab origine) or “those days” (illud tempus: the mythical time before time; time now and always) in their sacred New Year rituals. Eliade holds out the possibility that we modern people may come to see that the archaic “thirst for being,” which manifests as a “nostalgia for beginnings,” is still alive within us today and lies at the bottom of the need to participate in our contemporary secular New Year’s “profane rejoicings.” This, I believe, is what is behind our secular/profane New Year’s ritual. In other words (or lyrics):

"Behind the ritual, behind the ritual

You find the spiritual, you find the spiritual ...

Behind the rite, behind the ritual

Drinking that wine making time in the days gone by ...."

~ Van Morrison, 'Behind the Ritual'

See images below for what's really "behind the ritual" of our secular/profane New Year observance—rebirth and transcendence.

In archaic or ancient myth and ritual, the celebration of the New Year meant REBIRTH—for the sun and sun-gods, for nature, for the tribe or society, and for all human beings. It still does for traditional societies—and it still can be for modern ones. The concept of "rebirth" is an archetypal motif that applies to various levels of meaning; a common metaphor or literal event in myth and religion, in the "hero’s journey" in mythology, poetry, and romance, and even in the process of human creativity. Thus, even today, at this time in the cycle of the season, our contemporary New Year's celebrations still contain, however secularized and profaned, vestiges of the perennial need of humankind to suspend the flow of profane time and regenerate the mythic "time of beginnings" (in illo tempore ab origine); in other words, to make all things new—"to be born again."

(See images of Rebirth below.)

Prof. Eliade introduces his phrase illud tempus, to refer to the time of origins, the sacred time when the world was first created. The true homeland of the sacred is illud tempus ("those days;" a mythical time before time; time now and always), that ''other time'' of ultimate origins when the events recited in myth happened, when the gods made the world and heroes redeemed it, clearing the pathways to eternal return. Archaic religious man ("homo religiosus") accessed illud tempus whenever he ritually recited his cosmogonic myth, thereby reactuating the creation of his world. More generally, religious man needed to enter sacred time periodically because sacred time was what made ordinary, historical time possible. For the events of the sacred time of origins, enacted in ritual, were paradigms on which made the conduct of ordinary life was based.

<< Artwork behind text is entitled

"Illud Tempus the Dream World"

According to Prof. Elaide, the archaic New Year rituals produced rebirth in a mythic eternal present (in illo tempore, ab origine: “the time of the beginning,” the “great time” before history, “the mythic, transcendent time;” the illud tempus of “those days”). Therefore, to reiterate the argument of this musical essay series: even today, at this time in the cycle of nature, our contemporary New Year’s celebrations still contain, however secularized and profaned, vestiges of the perennial need of humankind to suspend the flow of time and regenerate the mythic “time of beginnings;” that is, to transcend time and make all things new—in other words, “to be born again.”

Thematic Images for New Year's Rebirth

The Cosmic Egg & the Broken Egg Symbolism of Rebirth

In a Buddhist text, the Suttavibhanga, the Buddha draws an analogy to the "Enlightened One" bursting the shell of ignorance with a chick breaking out of the egg. The laying of the egg is likened to the "first birth;" i.e., the natural birth of man. The hatching out corresponded to the supernatural birth of initiation, or "second birth." It should be noted that the Brahmanic initiation was regarded as a second birth. Furthermore, on the cosmic plane the supernatural birth of the Buddha is analogous to the breaking of the egg containing in germ the "firstborn" of the universe, which also has its origin in the "cosmic egg" of Brahmanic traditions, whence at the dawn of time there issued the primordial god of creation, variously named the "Golden Embryo," the "Father or Master of Creatures," or "Agni." This archetypal symbolism of the cosmic egg of rebirth is a variant of Prof. Eliade's writings about "archaic cosmogony."

In many of the major ancient civilizations, from the Mesopotamian to the Roman, their solar mythos meant that the concept of rebirth was associated with the return of the Sun at or around the time of the Winter Solstice, which also marked the beginning of the New Year. (This was the case for the Celtic peoples, as was covered in the GS's musical essay series for Samhain, the festival that marked the beginning of the dark half of the year and thus the "New Year.")

.jpg)

"Rebirth"

"Uterine and Thalassal regression"

(Pyschological theory of rebirth)

"Ascension and Rebirth"

Thematic Images for New Year's "New Beginnings"

Thematic Song Memes for New Year's "New Beginnings"

Thematic Images for Re-Inventing or Re-Imagining Yourself

Thematic Images for the Archaic Lunar Myth of Regeneration

According to Prof. Eliade, archaic lunar regeneration rituals consisted of what he terms as "lunar mysticism."

"Regeneration"

Thematic Images for the January "Wolf Moon"

THE WOLF MOON

In ancient times, it was common to track the changing seasons by following the lunar month rather than the solar year, which the 12 months in our modern calendar are based on.

According to the Old Farmer’s Almanac, because wolf packs howled hungrily amid the snows of midwinter outside Indian villages, this January full moon was called the “Wolf Moon.” In North America, the second full moon of the winter season is often called the “Wolf Moon.” (Other names are the "Moon After Yule," "Snow Moon," “Hunger Moon," or "Old Moon.") To some Native American tribes, this was the “Snow Moon,” but most applied that name to the next full moon, in February. Since the lunar (synodic) month is roughly 29.55 days in length on average, the dates of the full moon shift from year to year.

Supposedly, these full-moon names date back to when Native Americans lived in what is now the northern and eastern United States. Those tribes of a few hundred years ago kept track of the seasons by giving distinctive names to each recurring full moon. Those names were applied to the entire month in which moon each occurred. To be sure, there were some variations in the moon names but, in general, the same ones were current throughout the Algonquin tribes, from New England to Lake Superior. European settlers followed their own customs and created some of their own names. But while the "Wolf Moon" may have its roots in Native American history, it is inexplicably tied with folklore and storytelling from around the world.

THE SNOW MOON

The Snow Moon is the Full Moon in February, named after abundant snowfall in the Northern Hemisphere. It is also named for the heart of winter.

Some North American tribes named it the Hungry Moon due to the scarce food sources and hard hunting conditions during mid-winter, while others named it Bear Moon, referring to bear cubs being born this time of year. Celtic and Old English names for the February Full Moon are Storm Moon and Ice Moon.

The February 2026 Snow Moon will reach peak illumination at 2:09 p.m. PST and 5:09 EST on Sunday, February 1. February 1, 2026 brings the first Supermoon of the year and the brightest Full Moon of 2026. The Snow Supermoon will appear 14% larger and 30% brighter than an average Full Moon, creating a spectacular sight.

Thematic Images of the Archaic Hierogamy & Orgy

The New Year & Rebirth: the Hierogamy (Hieros Gamos or "Sacred Marriage")

"More generally, religious man needed to enter sacred time periodically because sacred time was what made ordinary, historical time possible. For the events of the sacred time of origins, enacted in ritual, were paradigms on which made the conduct of ordinary life was based. Thus, ordinary sexual unions between men and women were possible because of divine sexual union between god and goddess in the time of origins." ~Mircea Eliade

"Man only repeats the act of the Creation; his religious calendar commemorates, in the space of a year, all the cosmogonic phases which took place ab origine [from the origin]. In fact, the sacred year ceaselessly repeats the Creation; man is contemporary with the cosmogony and with the anthropogony because ritual projects him into the mythical epoch of the beginning — of the illud tempus, or 'those days.' … this reproduction [in ritual] made him contemporary with the mythical moment of the beginning of the world and he felt the need of returning to that moment as often as possible in order to annul profane time and its burden of memory and guilt; in other words, to regenerate herself or himself and the fallen world. . . . . The creation of the world, which took place, in illud tempore, at the beginning of the year, is thus reactualized each year. The hierogamy [the cosmic union of heaven and earth, male and female] is a concrete realization of the 'rebirth' of the world and man." ~Mircea Eliade

"Around 2000 BCE, the Babylonian New Year began with the first New Moon (actually the first visible crescent) after the Vernal Equinox (first day of spring). The festival observed the annual rebirth of the god of fertility, who was known as Tammuz in Babylon, the embodiment of rebirth in nature and son/consort of the goddess Ishtar. Their hierogamy symbolized the cosmic union of heaven and earth, male and female, and served as a concrete realization of the 'rebirth' of the world and man." ~Mircea Eliade

"The hierogamy was ritually observed in the annual rebirth of the god of fertility, who was known as Tammuz in Babylon, the embodiment of rebirth in nature and son/consort of the goddess Ishtar. Their hierogamy or hieros gamos symbolized the cosmic union of heaven and earth and served as a concrete realization of rebirth, giving the entire people a chance to begin again at the New Year." ~Mircea Eilade

"And when one of them meets with his other half, the actual half of himself, the pair are lost in an amazement of love and friendship and intimacy and one will not be out of the other’s sight even for a moment." ~Plato, The Symposium

"Marriage is no marriage that is not linked up with the sun and the earth, the moon and the fixed stars and the planets. Marriage is no marriage that is not a correspondence of blood … a communion of the two bloodstreams." ~D.H. Lawrence

Hierogamy & Orgy

According to Prof. Eliade, archaic mythico-ritual for the New Year reenacted the process of the original creation. In the beginning was chaos or formlessness, which was exemplified in many ways: “…fasting, confession, excess grief, joy, despair or orgy—all of them only seeking to reproduce a chaotic state from which a New Creation could emerge.”

Thus, the cosmos must be restored to the primordial unity from which it issued: “. . . it must return to ‘chaos’ (on the cosmic plane), to ‘orgy’ (on the social plane), to ‘darkness’ (for seed), to ‘water’ (baptism on the human plane, Atlantis on the plane of history, and so on). In short, according to the archetypal symbolism of lunar mythology, just like the moon, humankind must return to chaos, to orgy, to darkness, to water; it must be reabsorbed into the primordial unity from which it issued in order to be reborn in its fullness.”

“Marriage and the collective orgy echo mythical prototypes; they are repeated because they were consecrated in the beginning (“in those days,” in illo tempore, ab origine) by gods, ancestors, or heroes.”

When Prof. Eliade cites “marriage” as a repeating mythical example, he is referring to what is called the “sacred marriage,” technically known as the “hierogamy” (or hieros gamos). This, then, is what hierogamy or orgy had to do with the cosmogonic rituals commemorating the New Year.

The term "bacchanal," or "bacchanalia," essentially means "divine orgy" and comes from the name Bacchus, the Roman version of Dionysus. So technically the Greek versions of these orgies weren't called bacchanals, but are instead are referred to as the "Dionysian Mysteries."

Thematic Images for the Shaman's World Tree (Axis Mundi)

%205.jpg)

Shaman is named from the Tungus tribes of Siberia, and it refers to a man or woman with a special spiritual power. Shamans were visionaries, healers, and spiritual consultants, who often worked in a trance state. Shamanism is a way of viewing reality, and a method or technique for functioning with the view of reality. The shaman sees the world differently from other men and women, and his/her personal experiences, in the universe, seem to transcend those of other people

Prof. Mircea Eliade identifies the primary ontological trait of archaic peoples as a "nostalgia for beginnings." Thus, the argument of this musical essay series on the New Year is that we modern people have not altogether lost this kind of arcahic "nostalgia. Indeed, it is manifesting today in the form of a longing for our own pre-historic cultural beginnings—"nostalgia for the lost archaic" (as visionary philosopher Terence McKenna has termed it).

According to Prof. Elaide, the archaic New Year rituals produced rebirth in a mythic eternal present (in illo tempore, ab origine: “the time of the beginning,” the “great time before history,” “the mythic, transcendent time;” the illud tempus of “those days”).

To see what McKenna means by "The Archaic Revival" and its "nostalgia for the lost archaic," click on button.

A glossary of the major terms used by Prof. Eliade pertaining to the archaic worldview.

Technical Terms

Anthropogony: an account of the origin of humanity.

Autochthony: the origin or birth in the land itself; that which is indigenous or particular to a certain place.

Cosmological: having to do with the universe, its structure.

Cosmogony: a mythic model of the origin and evolution of the cosmos; the birth of the cosmos and order; the way things came to be.

Eschatological: relating to the ultimate destiny of mankind and the world.

Eschatology: (lit. "study of the last") a part of theology and philosophy concerned with what are believed to be the final events in history, or the ultimate destiny of humanity; "the end of the world."

Eschato-cosmological: the cosmology of the end of time.

Hierogamy: (hieros gamos, "sacred marriage") the ritual marriage between a deity and a mortal Hierophany: (from the Greek roots hieros, meaning “sacred” and phainein, meaning “to reveal” or “to bring to light,” as in our word epiphany) a manifestation or breakthrough of the sacred into the world. In the hierophanies recorded in archaic and ancient myth, the sacred appears in the form of ideal models, or “archetypes” i.e., the actions of gods, heroes, ancestors, etc.

Mythico-ritual: a ritual as a repetition of original (mythic) events; a ritual based upon mythic events, re-enacting and re-actualizing the original cosmogonic act of creation, especially through the formulas that are recited during these ceremonies.

Ontological: pertaining to that which is real, that which exists.

Ontology: a mythic model of the nature and relations of being.

Ontophany: a manifestation of what is real.

Paradigmatic: in the manner of an authoritative example.

Phenomenology: the description of appearances/phenomena/facts.

Sacralize: to render or make sacred.

Sidereal: relating to stars or constellations, relative to the heavens.

Soteriological: having to do with salvation or a savior.

Telluric: terrestrial; pertaining to earth and its energy.

Theophany: a manifestation of the divine.

Valorization: the process of making or recognizing something to be important or valuable; to exalt.

Latin Terms

ab origine : from the origin; towards the beginning.

ab initio : the moment of creation.

axis mundi : cosmic pillar; axis of the universe; the center of the world around which everything revolves and by which the different realms of the universe are connected.

coincidentia oppositorum : coincidence of opposites.

fons et origio : the source and origin; primary cause.

homo religiosus : humans (particularly, archaic humans) as inherently religious beings.

illud tempus : that time, or "those days;" a mythical time before time.

imago mundi : the model of the world as it looks.

in aeternum : in eternity.

in illo tempore : in that time before history; mythic, transcendent time.

in illo tempore, ab origine : the time of the beginning; the "great time" before history; mythic, transcendent time; "once upon a time."

incipit vita nova : beginning of new life; rejuvenation of life itself.

in principio : in essence, in truth, the way things really are.

numen : (numinous) divine, powerful, sacred; overwhelming sense of holy.

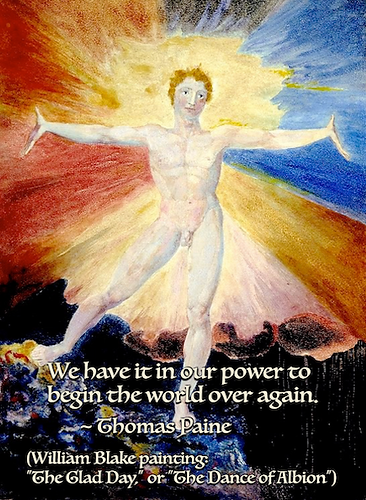

In honor of Martin Luther King Jr Day, the Gypsy Scholar has created this meme using Dr. King's words. It is significant that I have chosen something Dr. King said that coincides with my theme of the New Year--"new world."